by Robert Buchanan

Deathtrap (1982)

Directed by Sidney Lumet

Written by Ira Levin, Jay Presson Allen

Produced by Burtt Harris, Alfred De Liagre Jr., Jay Presson Allen

Starring Michael Caine, Christopher Reeve, Dyan Cannon, Irene Worth, Henry Jones

"The most important thing in acting is honesty: if you can fake that, you've got it made."

--George Burns

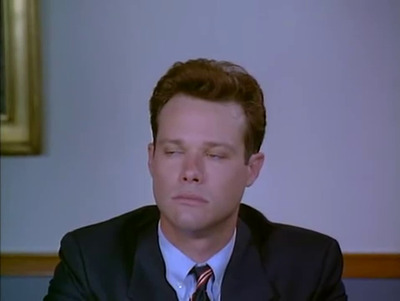

For four flagrant flops in consecution, their famed but fading playwright (Caine) of thrillers is driven to dejection, desperation and distraction of a kind inspiring the murderous machination to invite a sometime student (Reeve) who's penned and posted him a first-rate foray in his manner to his home for collaborative colloquy, so to dispatch the gifted greenhorn with an article from his panoply of stage props and antique weaponry, and crib the thriller as his own to revive his career and finances. Attic dialogue, anfractuous artifices and artful auguries of Levin's hit stage play are preserved and magnified in this penultimate picture of Lumet's second winning streak, as sable in its hilarity as it's diegetically flexuous, defying and denying prevision for initial viewers first with a perverse masterstroke at midpoint, then a succession of vicissitudes as both the sinuous plot and that of its culprit's eponymous work unfold pari passu, complicated by the homicidal author's squirrelly, cardiopathic wife (Cannon) and a meddlesome, clairvoyant celebrity (Worth) of Netherlandish extraction. Caine was cast choicely in the seething, sulky, scheming, creepy lead opposite Reeve, whose typecast stature as cinema's charming, caped darling made selection of a wickedly rigorous role as impressive for his professional daring as his patently protean proficiency. "To show you any more would be a crime," proclaims this movie's trailer in sincerity; that first of several twists may not shock with the potency it had over three decades ago, but the cinematic dash with which Lumet and continually contemporaneous collaborator Allen adapted Levin's ingenious source elevates it in transition to the filmic medium. It's shot, played and cut with such irresistible, hysterical, cutthroat, playful panache, you almost can't envision its proscenium!

Recommended for a double feature paired with A Shock to the System.

The House of the Devil (2009)

Written and directed by Ti West

Produced by Josh Braun, Larry Fessenden, Roger Kass, Peter Phok, Derek Curl, Badie Ali, Hamza Ali, Malik B. Ali, Greg Newman

Starring Jocelin Donahue, Tom Noonan, Greta Gerwig, Mary Woronov, A.J. Bowen

"That which is new can only be effective in the context of what is old and familiar."

--Krzysztof Penderecki

They're almost as often botched as assayed: period pictures representing the 1980s seem unattainable undertakings for millennial filmmakers, their generation virtually defined by inauthenticity and the pervasive nescience of their precious sociocultural tabula rasa. At worst, even the era's trappings are inadequately recreated: rather than earth tones, neon and pastel accents and accoutrements predominate in '82; leg warmers are garbed glaringly as late as '88; working- and middle-class households enjoy amenities of appliances and entertainments they couldn't possibly yet afford; no residua of the '70s are observable, be they tacky decals, ill-conceived drapes of pea-green and brown paisley or stripes, or enduring, smutty shag sprawling wall to wall. Worse, when an informed crew have replicated interiors, vesture, chattels, etc. so well as to excite the very zeitgeist for those of us who remember, the fastidious facade is shattered the moment an actor utters either parlance scripted in poor imitation or a contemporary vernacular voiced via uptalk and other insufferable habitudes.

West and his crew clothed his slow, steady exploitation of the bygone satanic panic with a rare verisimility to polish one of a few top-notch American horror flicks produced during the aughts. Its scenario would in lesser hands seem like hackery: yearning for privacy, repulsed by her slatternly roommate and desperate to secure her first month's rent for lodging at an inviting rental house, a cute collegian (Donahue) leaps at the opportunity to babysit for an elderly couple (Noonan, Woronov) with an avidity abated by their conditional oddities, but her dubiety and suppressed suspicions prepare her neither for their grisly intrigues nor her Luciferian fate, engrossed upon a lunar emersion following the night's total eclipse. Sagely refraining from complete pastiche, West instead incorporates techniques popularized in the '70s and early '80s into his vigorous idiom. Frames frozen during opening credits, lingering close-ups and zooms of varied velocities amplify tension, stress vehemence and arrest the eye. He's incapable of a poor shot -- whether still or creeping thwart and through hallways, enfilades and immaculately dressed rooms -- and maintains pace and consistency by cutting his faintly grainy, chromatically rich Super 16 footage with a punctilious art worthy of his script, complete for its shades of portent and playful, preordained protagonist's expatiating exploration of her employers' mansion to establish spatial and tonal parameters, and raise the eyebrows of those most wakeful in her audience. Notwithstanding a few anachronous elements (a payphone accepting quarters, car alarm and latter-day faucets), this picture's immersive for Jade Healy's transformative production design, Robin Fitzgerald's charming costumes, and meticulous art direction courtesy of Chris Trujillo, all complemented by Mike Armstrong's memorable opening tune and fantastic faux newscasts helmed by second unit director/sound designer Graham Reznick. Only a few lines delivered with present intonation remind one fleetingly of Donahue's contemporariness, and her achingly lovely, post-Celtic phenotype is as becoming of the era as her high-waisted bluejeans or knit scarf. She's all but perfect in the role of unwitting tour guide and victim, but still spicily upstaged in their every shared scene by indie darling Gerwig as her crude, cheeky, feathered best friend. Both are foils for Noonan and Woronov, veterans of creepy roles who expertly enact a gentility veiling subtly subjacent menace. Disregard naysayers who misrepresent West's cunningly cultivated suspense as longueur by omitting one of the best jump scares at which you'll ever flinch, and that his prolonged preludes lead to a strobing, severely stridulous and sanguineous climax. Both the gently foreboding, pianistic themes and quintet's strepent strings of Jeff Grace's score, as well as adjunct music and painstaking audio design by Reznick and foley artist Shaun Brennan, intensify without disrupting disquiet of many key scenes. Few of West's Anglophone coevals (Carruth, Mitchell, Cosmatos) evince an apprehension of their medium's dramatic, thematic and technical dynamics so penetrating as his; well aware that the devil's in the details, he, Reznick, et al. are just old enough to faithfully recall and evoke the ethos of '83, when society was still sufficiently sane and cohesive to judge these atrocities shocking.

Recommended for a double feature paired with The City of the Dead, Rosemary's Baby, Black Christmas, or Beyond the Black Rainbow.

Destiny (1921)

Directed by Fritz Lang

Written by Fritz Lang, Thea von Harbou

Produced by Erich Pommer

Starring Lil Dagover, Bernhard Goetzke, Walter Janssen, Eduard von Winterstein, Rudolf Klein-Rogge, Paul Biensfeldt, Károly Huszár, Hans Sternberg, Karl Rückert, Erika Unruh

Upon his visitation in a pastoral town, stern, somber Death (Goetzke) pays handsomely to lease a parcel alongside a cemetery that's been designated for its graveyard's expansion, where he erects a sepulchral stronghold inaccessible to all save a doughty, doleful damsel (Dagover) whose young fiancé (Janssen) he's consigned to the hereafter, and for whose restoration she obtests. So moved is the Grim Reaper by her impassioned impetration that he challenges her for a chance at her wish: incarnated as treble doxies of as many men soon to meet their end, they may be reunited if she can rescue but one of them. In a Persian city of strident muadhdhins, whirling dervishes and veiled beauties, the sister (Dagover) of a cruel caliph (Winterstein) struggles to rescue her secret lover, a Frank (Janssen) pursued by authorities after daring to visit her in a mosque during Ramadan. Lusty, conspirative Venice is the backdrop of a tragedy whereby a corrupt councilman (Klein-Rogge) designs to dispatch during Carnival the sweetheart (Janssen) of a noblewoman (Dagover) to whom he's hatefully engaged. Finally, Dagover and Janssen are enamored assistants to a preeminent magus (Biensfeldt) who's commissioned to entertain China's tyrannical Emperor (Huszár) on the occasion of his birthday in exchange for his life; when the despot claims her and imprisons her man, she may need more than magic to save them both. For its innovatory set design, Orientalist and Italian charms, dated yet vivid special effects and Lang's captivating composition, his fatalist, fabular fantasy is nearly as impressive as it was a century ago. Moreover, its presentation of morbid theurgy is among the medium's first and best, serving to influence many posterior. Creating her woebegone, mettlesome maiden in broadly histrionical strokes, Dagover inhabits another of many sacrificial heroines prevailing in Weimar cinema, and Goetzke's implacably forbidding as a solemn foil to her often hysterical fervor. Exciting, funny, touching, poetic and rich with symbolic auspices, Lang's centennial classic evokes a bittersweet poignance reliant on the verity of its burden: ever salvational, love may endure a quietus that it can never defeat.

Recommended for a double feature paired with The Seventh Seal.

Evolution (2015)

Directed by Lucile Hadzihalilovic

Written by Lucile Hadzihalilovic, Alante Kavaite, Geoff Cox

Produced by Nicolas Villarejo Farkas, Ángeles Hernández, David Matamoros, Julien Naveau, Sylvie Pialat, Benoit Quainon, Sebastián Álvarez, John Engel, Genevieve Lemal

Starring Max Brebant, Roxane Duran, Julie-Marie Parmentier, Marta Blanc, Mathieu Goldfeld, Nissim Renard

Distant from lush forests where the little ladies of Innocence were secluded, Hadzihalilovic's eerily, elegantly elliptic second feature probes the seaboard secrets of an austere, insular village. Similarly severe women domiciled there with young boys in their care feed a vermicious stew and administer an inky medicine to their charges, who are subjected to strange experiments in a dank, nearby hospital where they're eventually committed. One peculiarly inquisitive tad (Brebant) among them discovers another boy's corpse in the reef of his island's bight, then witnesses the surrogate mothers' bizarre, nightly, coastal congress, realizing too late the danger his keepers pose. For its economy, dialogue is essentially effective from the mouths of the directress's naturalistically convincing cast, and she wisely paces this quiet nightmare elicited from a juvenile trepidity with exquisite deliberation, introducing her setting's seascapes and landscapes in panoramas, then focusing on swimming and swaying benthos, tenebrious revelations and subtly suggestive gestures that communicate perhaps more than any conversation. As in her debut, water's here a literally and metaphorically transitional medium, almost so ubiquitous in the umbratile hospital where our protagonist is befriended by a sympathetic nurse (Duran) as on the strand where weltering breakers underscore with Jesús Díaz's and Zacarías M. de la Riva's perturbing, poignant music portent and peril. Hadzihalilovic's superbly stygian, spartan fantasy proposes a societal and interspecific parasitism, and that mercy may not be exclusive to humanity.

The Romance of Astrea and Celadon (2007)

Directed by Éric Rohmer

Written by Honoré d'Urfé, Éric Rohmer

Produced by Françoise Etchegaray, Philippe Liégeois, Jean-Michel Rey, Valerio De Paolis, Enrique González Macho, Serge Hayat

Starring Andy Gillet, Stéphanie Crayencour, Cécile Cassel, Serge Renko, Véronique Reymond, Jocelyn Quivrin, Mathilde Mosnier, Rodolphe Pauly, Rosette, Arthur Dupont, Priscilla Galland

"Where love is, no disguise can hide it for long; where it is not, none can simulate it."

--La Rochefoucauld, Maxims

Love rends, mends and fortifies impassioned, shepherding Foréziens of the 5th century for folly and affection in this charming condensation of d'Urfé's classic, colossal comedy, L'Astrée. Dupery by one flirt (Dupont) incident to the fierce fancy of another (Galland) stings a jaundiced shepherdess (Crayencour) to jilt her highborn paramour (Gillet), who in rash heartbreak attempts to drown himself in the Lignon. A trio of nymphs discover him ashore downriver, then in their castle quarter and nurse to health the sheepherder with whom their doyenne (Reymond) finds herself unreciprocally enamored. Her fellow noblewoman (Cassel) frees the herdsman from immurement, then with her druidic uncle (Renko) heartens and edifies him before a Mistletoe Festival, where the adoring drovers may be reunited by an eccentrically epicene ruse. Rohmer's casual, conversational, implicitly Christian manner is perfectly suited to the marquis de Valromey's novel, from which all save a few of many parabolic excursus are here excised. Those judiciously retained vividly illustrate values of the seventeenth century transposed by its comte de Châteauneuf to the fifth: a dispute between our lovelorn protagonist's stalwartly monogamous brother (Quivrin) and a ludic, licentious troubadour (Pauly) pits an amative argument for fidelity against hedonistic casuistry in promotion of polyamory; at a sanctified grove, Renko's delphic druid skews from physiolatry to certify a monotheism for Teutates by relegating lesser gods as mere physitheistic personifications of virtues, and posits a consubstantial divinity that prefigures Christianity's Holy Trinity. Two of the director's perpetual performers won't be overlooked by fans among his lovably lovely leads and their photogenic co-stars: one in three nymphs is Rosette, while Marie Rivière can be glimpsed as the reveling mother of Gillet's straying swain. Late in life and art, Rohmer couldn't have abridged a better story to example his final insistence that love's as much fated as physical, or spiritual as sensual.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Love in the Afternoon or The Marquise of O.

The Wailing (2016)

Written and directed by Hong-jin Na

Produced by Suh Dong Hyun, Ho Sung Kim, Xian Li, John Penotti, Robert Friedland

Starring Do-won Kwak, So-yeon Jang, Jun Kunimura, Woo-hee Chun, Hwan-hee Kim, Jung-min Hwang, Kang-gook Son, Do-yoon Kim, Jin Heo, Seong-yeon Park, Chang-gyu Kil, Bae-soo Jeon, Mi-nam Jeong, Gwi-hwa Choi

"It is a sin to believe evil of others, but it is seldom a mistake."

--H. L. Mencken, A Little Book in C Major, 1916

Attentive viewers (especially those versed in Catholic scripture and Korean folk sortilege) will best appreciate the innuendo of Na's creepingly circuitous chiller, but such insights can't conduce prospicience of its outcome. A village's police are confounded when locals are sanguinely slain by ensorcelled relatives, who then succumb to grisly afflictions. This unaccountable spate coincides with sightings of an earthy, impertinent beauty (Chun) and an old Japanese (Kunimura), the latter of whom is a subject of macabre and concordant scuttlebutt. When the daughter (Kim) of the force's sluggardly sergeant (Kwak) manifests incipient behavioral and dermal symptoms common to the doomed murderers, he's desperate to interrogate both strangers. Refreshing restraint and professional calculation characterize Na's masterly direction, which discloses minimally in slow zooms and pans as his plotted convolutions gradually unravel, without ever relaxing the intensity of his drama or action. By Kyung-pyo Hong's photography, South Korea's sylvestrian beauty is blazoned in establishing landscapes, and many figures are strikingly limned in silhouette and shadow. The cast is exceeding, but its concerted excellence admits of certain standouts. Kunimura's internationally recognized for his versatility as villains and victims alike; his stony stare and mutable mien here sustain his loner's imperative mystique. A dynamically antipodal approach by Hwang to a shaman hired by Kwak's deviled officer informs his energic exorcism preceding the movie's centerpiece, a clamorously violent, elaborate, apotropaic rite not to be forgotten. Kim's metamorphosis from sweet schoolgirl into maledicted malefactor recalls Linda Blair's most famous role -- and she interprets it with analogous anguish and audacity. All of the seven deadly sins are committed, but their significance is primarily representative. Na's moral compass is pragmatically oriented, indicating how obtuse skepticism, inaction, misjudgment, and hysteria result in a small, appalling tragedy. These misdeeds frustrate the talismanic and lustrative white magic that might've dashed demonomagy conjured by and thriving for vice, folly, and confusion.

Recommended for a double feature paired with The Exorcist.

The Acid House (1998)

Directed by Paul McGuigan

Written by Irvine Welsh

Produced by David Muir, Alex Usborne, Carolynne Sinclair Kidd, Colin Pons

Starring Stephen McCole, Maurice Roëves, Alex Howden, Annie Louise Ross, Garry Sweeney, Jenny McCrindle, John Gardner, Stewart Preston, Simon Weir; Kevin McKidd, Michelle Gomez, Gary McCormack, Tam Dean Burn; Ewen Bremner, Arlene Cockburn, Martin Clunes, Jemma Redgrave

Perhaps because he scripted this raunchy, riotous, revolting adaptation of three among twenty-two stories from his eponymous anthology, it's likely the best picture based on Welsh's fiction. During his life's last, worst day, a footballing loser (McCole) is cut from his carousing league, by his deviant dad (Howden) dislodged, nubile girlfriend (McCrindle) jilted, manager (Preston) axed and a police sergeant (Gardner) brutalized, then confronted in a pub by cantankerous God (Roëves), who transmogrifies the swilling dud in disgust for his shortfall of ambition. Newly mutated, the bitter flop of The Granton Star Cause exacts petty vengeance with newfound stealth, but not with impunity. If he wasn't such A Soft Touch, a gutless, married father (McKidd) wouldn't suffer repeated humiliations by his slatternly wife (Gomez), or the loutish, lascivious lunatic (McCormack) with whom she's clamantly cuckolding him, whose varied, parasitic impingements aren't possible without a perfect poltroon. A tab of potent LSD and bolts of lightning swap the minds of a doltish football hooligan (Bremner) and a hideous, vinyl neonate at the moment of exchange born to an insufferable, upscale married couple (Clunes, Redgrave). Reveling in this supernatural infantilization, his devoted girlfriend (Cockburn) designs to remold him into a better person, but a casual encounter between the commuted clods intervenes in The Acid House. Consistently comical and leavened with psychedelic fantasy, this felicifically foul time capsule from Scotland's late '90s dramatizes Welsh's navel-gazing prime with fine, funny, filthy performances against squalid locations in Glasgow and Edinburgh, and good musical selections by The Pastels, Glen Campbell, The Chemical Brothers, Nick Cave, The Verve, etc. Viewers unaccustomed to nearly unintelligible Glaswegian accents will need subtitles.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Trainspotting.

Batman: The Movie (1966)

Directed by Leslie H. Martinson

Written by Lorenzo Semple Jr.

Produced by William Dozier, Charles B. Fitzsimons

Starring Adam West, Burt Ward, Lee Meriwether, Burgess Meredith, Cesar Romero, Frank Gorshin, Alan Napier, Neil Hamilton, Stafford Repp, Reginald Denny

Holy collusion! When the Penguin (Meredith), Joker (Romero), Catwoman (Meriwether) and Riddler (Gorshin) assay to abduct nine delegates of an international security council and eliminate Batman (West) and Robin (Ward) with a weaponized dehydrator that reduces its targets to colored dust, the dynamic duo investigate and confront those four flamboyantly fiendish felons with their arsenal of chiropterously-themed weapons, vehicles, gizmos and solutions for every eventuality! Effectively an extended, widescreen episode of the gaudily deadpan, televised farce, this theatrical feature's dotted by Semple with an argosy of his eccentricities: sight gags, cockamamie contraptions and punch lines integral to its plot; amusingly aimless extravagances; historical and literary references; fulsome fracases; abundant adnomination. Halting West and squawking Meredith are parceled and optimize his funniest dialogue, but all of these wry heroes and manic rogues make every minute hilarious. In routine conformity to the series' style, Martinson frames the scoundrels exclusively in Dutch angles at their hideout, but reserves those exclamatorily onomatopoeic captions for a climactic melee upon a spheniscine submarine. Fans of the series have naturally seen this; anyone else partial to high camp is sure to adore it.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Superman III or The Adventures of Buckaroo Banzai Across the 8th Dimension.

Bluebeard (2009)

Directed by Catherine Breillat

Written by Charles Perrault, Catherine Breillat

Produced by Sylvette Frydman, Jean-François Lepetit

Starring Lola Créton, Dominique Thomas, Daphné Baiwir, Marilou Lopes-Benites, Lola Giovannetti, Farida Khelfa, Isabelle Lapouge, Suzanne Foulquier, Laure Lapeyre

"Adolescence begins when children stop asking questions -- because they know all the answers."

--Evan Esar

Mutual malice differentiates Breillat's companion to her surpassing, subsequent The Sleeping Beauty from most other portrayals of the gory, Gallic fairy tale. Two little sisters of the Fourth Republic sport with stories while browsing through a cluttered attic, where the bratty junior (Lopes-Benites) frightens her sensitive senior (Giovannetti) with a reading of Perrault's parable. However, this telling strays significantly from that fabular classic: lovely sororal teens (Créton, Baiwir) boarded as a nunnery's oblates in the late seventeenth century are dismissed by their abbess (Khelfa) after their father dies by his selfless heroism; his creditors leave they and their mother (Lapouge) in penury as abject as their bereavement, but Créton's demoiselle leaps at a contiguous opportunity to wed a bloated, barbate count (Thomas) infamous for his suspected uxoricides. Once married, she luxuriates in his opulent castle while becharming her nobleman, until he intrusts to her his castle's keys ere his leave with a forbiddance not to enter one of its many rooms. Every tableau of this picture and variance from its literary source breathes symbolical significance, and Breillat's fans will readily recognize her idiomatic emblems in slaughtered fowl and accumbency abed, but the key to its burden resides in the thematic equipollence of its eponymous, crinally converse sisters. For art and awareness, the presumed "porno auteuriste" again succeeds where so many other feminist filmmakers stumble, not least because her acknowledgement of biopsychology negates the fantastic self-aggrandizement and victimization that ruined their movement. Any of Hollywood's pampered, obese activists would've distorted this folktale as an example of thwarted patriarchy, but her barbarous lord and guileful bride instead effectuate gendered modes of rapacity, reflecting an incidental intimacy and attendant regret.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Breillat's The Sleeping Beauty or those best among numerous adaptations of Bluebeard.

Brother (1997)

Directed and written by Aleksey Balabanov

Produced by Sergey Selyanov

Starring Sergey Bodrov, Yuriy Kuznetsov, Svetlana Pismichenko, Viktor Sukhorukov, Mariya Zhukova, Vyacheslav Butusov, Irina Rakshina, Sergey Murzin, Tatyana Zakharova

"I knew wherever I was that you thought of me, and if I got in a tight place you would come - if alive."

--William Tecumseh Sherman, letter to Ulysses S. Grant, 1864.3.10

Not to be confused with Kitano's underwhelming, cross-cultural Yakuza flick shot stateside a few years later, Balabanov's grimy crime drama was a domestic hit as much for its depiction of Russia's chaotic zeitgeist as its crafty economy. At the insistence of their mother (Zakharova), a tough, resourceful young veteran (Bodrov) of the First Chechen War peregrinates to St. Petersburg to reunite with his big brother (Sukhorukov), a freelance assassin employed by local gangsters. For his enterprise, martial invention and tactical cunning, he betters his sibling's success as a slippery gun for hire, but soon finds that urban life is as spiritually insidious as remuneratory. When he isn't greasing culprits of low character, the gifted gunsel beds a battered housewife (Pismichenko), troops with a trendy druggie (Zhukova) and an aging, weathered, German chapman (Kuznetsov) who resides in a Lutheran cemetery, and fixates on, attends a performance by and encounters at a party his new favorite band, Nautilus Pompilius, who provide most of the picture's music. Armed to kill with discrimination checked by rectitude and a CD steadily spinning waist-high in his Discman (an accessory of any upright young man in the '90s), Bodrov's felon is for his farouche humor, adaptability, fraternal fidelity and uncertain circumstances an embodiment of the plights and pertinacity that typified the ethos of young Russians during their nation's post-Soviet tumult. Practiced portrayals and St. Petersburg's backdrop contribute to this little landmark's plausibility, but its youthful audiences came for excitement and returned to see one of their own heroized for a principled criminality.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Three Days of the Condor, Le choc, or Brother 2.

Cube (1997)

Directed by Vincenzo Natali

Written by Vincenzo Natali, André Bijelic, Graeme Manson

Produced by Mehra Meh, Betty Orr, Colin Brunton

Starring Nicole de Boer, David Hewlett, Maurice Dean Wint, Nicky Guadagni, Andrew Miller, Wayne Robson

Natali's cult favorite requires little introduction, but that anglophonic score who've yet to see it probably won't be disappointed by this misadventure of a seasoned recidivist (Robson), police officer (Wint), draftsman (Hewlett), student (de Boer), physician (Guadagni) and autist (Miller) mysteriously waking within and collectively struggling to escape from a massive matrix comprised of interconnected cubic rooms. For whoever can decipher them, the integral or Cartesian signification of triplex trinumerals printed within each room's six doorways seemingly signify which contain deadly traps not necessarily more hazardous than the strange sextet's internecine umbrage and paranoia. Not as sophisticated as it's become, Natali's tolerable direction isn't half as imaginative as his, Bijelic's, and Manson's script, as much for its geometrically Gordian setting and diegetic twists as its characterizations of distinct personal types altered by extreme pressure in prickly situations: the pessimism of Hewlett's omega gifts him with a surprising fortitude; at first wholly dependent, de Boer's beta proves herself as essential a mathematician as an intermediary; Robson's sigma is laid low early to leave the survivors without their most resourceful member; at first a natural leader, Wint's alpha is reduced by petty indignation and encroaching madness into a Procrustean tyrant; Guadagni's skittish, shrewish gamma unearths an unexpectedly quasi-maternal affection for Miller's autistic savant, who's in possession of a vital verve he can't use alone. Against Jasna Stefanovic's superbly impersonal, industrial production design, the cast's porcine performances contrast oddly well, and for what they lack in realism and restraint, they compensate with photogenic presence. Comparably, CG by effects firm C.O.R.E. is noticeably artificial, but smartly designed. This sleeper found its audiences via home video and nonstop cablecast on the Sci-Fi Channel in the '90s; it's now just as omnipresent on streaming channels and worth watching -- first for fun, then again for details you might've missed.

Encounters at the End of the World (2007)

Directed and written by Werner Herzog

Produced by Randall M. Boyd, Henry Kaiser, Tree Wright, Julian P. Hobbs, Andrea Meditch, Erik Nelson, Phil Fairclough, Dave Harding

Starring Werner Herzog, Samuel S. Bowser, David Ainley, Clive Oppenheimer, William McIntosh, Olav T. Oftedal, Regina Eisert, Libor Zicha, Kevin Emery, David R. Pacheco Jr., Jan Pawlowski, Peter Gorham

For mundivagant Herzog, Earth's final, frigid frontier was an inevitable destination nearly a century after explorers Roald Amundsen, then Robert Falcon Scott planted their respective Norwegian and British flags at that desolate destination. This documentary's finest sights are transcendent for meditative shots of chaste polar landscapes and watery wonders, but it's too often derailed when Herzog's narration or worst subjects digress absurdly. Vintage footage of the terminal impasse that stymied Ernest Shackleton's Imperial Trans-Antarctic Expedition and destroyed his ship Endurance, and the subsequent hardship of his crew's grueling passage to South Georgia Island is cleverly juxtaposed with that of a humongous omnibus driven for the convenience of passengers at McMurdo Sound by one Scott Rowland, who relates one of his adventures in Guatemala. Rowland and McMurdo station's forklift operator Stefan Pashov are two of numerous roving professionals who seem to constitute a majority of Ross Island's population; the latter fancifully proposes that zetetics are by commonalities impelled to convergence at their southernmost post. In the austral summer's five months of constant daylight, the station's industrial hideosity contrasts with the stark beauty of Ross Island and the Ross Sea. To escape it and its amenities (dully comfortable residential quarters, a bowling alley, an aerobic studio) that repulse him, Herzog departs for several field camps after one Kevin Emery mandatorily trains him and other newcomers in the rudimentary construction of snowy trenches and igloos (wherein trainees are required to sleep overnight) and cooperative navigation via lifeline in conditions where visibility and audibility are null. Nutritional ecologist Olav Oftedal and his crew study the dietary peculiarities of docile, roly-poly Weddell seals, extracting with a forcible yet harmless method from nursing cows a milk of uncommon viscosity and chemical composition noted by physiologist Regina Eisert. An utter silence common to the vicinity of Oftedal's station is often broken by phocine vocalizations in waters six feet beneath it: resonant whirrs, burbles, blips and howls that could be mistaken for those generated by an analog synthesizer. At the mainland's coast, cellular biologist Samuel Bowser quietly exudes either anxiety or melancholy on the occasion of his last antarctic dive, during which he observes exotic fauna and flora in gelid immersion. From another dive ensuing toilsome drilling and detonation elsewhere, three captured specimens are genetically determined by zoologist Jan Pawlowski to be of theretofore unknown foraminiferal species. Slow and static shots of Shackleton's hutch reveal it unchanged over a century, one of a faded empire's innumerable proto-civilizational relics. Further, a monument erected alongside the numerous flags raised at the south pole commemorates Amundsen's and Scott's pioneering attainments...though Herzog can't help but bemoan this progress and a presumptive loss of its site's pristine serenity, a value that's never qualified. Cocks of a waddle wait on eggs for hens to return at Cape Royds, where Herzog interviews eremitic marine biologist David Ainley, who graciously replies to an asinine question regarding homosexual penguins with his observations of polyamory and transactional congress in the colony. A visit to Mt. Erebus finds volcanologist and geochronologist William McIntosh displaying and demonstrating the functionality of a rugged observational camera designed to withstand explosions, emplaced to monitor the volcano's lava lake. Tasked with examination of the volcano's gaseous emissions, his subordinate colleague Clive Oppenheimer historically contextualizes the relative severity of known volcanism. Our impressionable filmmaker's existential despondence, now inspired by climatic pseudoscience repeatedly reworked and consistently unproven over the course of a half-century, spoils what could've been a pleasantly amusing scene: in a frozen subterranean passage leading to the precise center of the South Pole, two workers deposit a frozen sturgeon in a niche opposite another garlanded with strung popcorn, containing little floral prints...while Werner the doomsayer verbalizes a stale, silly scenario in which extraterrestrials visit the niche perhaps a millennium following mankind's extinction. Finally, physicists led by Dr. Peter Gorham launch an enormous balloon to loft instruments constructed to detect neutrinos above any distractions of terrestrial electricity.

Sublimed by the ethereal vocal plangency of Dragostinov's Planino Stara Planino Mari performed by The Philip Koutev National Folk Ensemble, and Alexander Sedov's rendition of Bortnyansky's Retche Gospod Gospodevi Moyemu, among others, this picture's underwater and underground highlights are extraordinary for deft exhibition of the former's magnificent aquatic biota, and in both icy formations submersed and caverned -- those latter accessed though fumaroles by McIntosh's spelunking team. If these speechless sequences characterize Herzog at his best, redundant commentary by his interviewees and his pestilentially pessimistic narration represent the worst he has to offer. Some of Pashov's philosophical musings are mildly interesting, while others are as negligible as the dreams that glaciologist Doug MacAyeal recalls before addressing his far more intriguing surveyal of a calving iceberg (B-15). David Pacheco is McMurdo station's demonstrably adept plumber, who bloviates about his allegedly Aztec ancestry and more environmental paranoia, but not his duties there. Linguist William Jirsa recounts how he came to keep the station's greenhouse, and he's only marginally more occupying than Karen Joyce, whose African and South American extravagations decades before were surely as perilously imprudent as they're tediously told. Earlier scenes show two seemingly pathetic penguins mysteriously, intractably bound for the mainland's interior and their likely quietus; one can imagine Herzog's apposition of these apparently disoriented birds with the errant baizuo vacuously reporting their own misadventures. Those subatomic particles that Dr. Gorham tracks and describes are enthralling, but his own gushing fascination with them is not. One bright exception is Libor Zicha, a machinist still visibly haunted by trauma suffered during the Cold War, who keeps an impressively comprehensive survival kit in a rucksack at his side at all times. An extraneous interview of irritatingly ingenious publicity hound Ashrita Furman comprises a most glaringly inapposite aside.

This might've been another of Herzog's documentary masterworks, but it's marred by the trendy and sentimental faults that so endear it to Anglophones. His undue familiarity, rambling, risible ruminations and desultory indulgences might be apropos to one of Errol Morris's features, but for them this 100 minutes is a fifth padded and hardly so graceful than it should be. Unlike the foregoing sacred music, Henry Kaiser's and David Lindley's score is almost unbearably grating. So untypically personal, unprofessional and subjective is it that its conclusive dedication to Roger Ebert comes as no surprise.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Into the Inferno or Cave of Forgotten Dreams.

The Enigma of Kaspar Hauser (A.K.A. Every Man for Himself and God Against All) (1974)

Directed by Werner Herzog

Written by Werner Herzog, Jakob Wassermann

Produced by Werner Herzog

Starring Bruno Schleinstein, Walter Ladengast, Michael Kroecher, Brigitte Mira, Enno Patalas, Hans Musäus, Gloria Doer, Volker Prechtel, Volker Elis Pilgrim, Clemens Scheitz, Henry van Lyck, Willy Semmelrogge

"[W]e shall never succeed entirely in extirpating from the heart of man this original credulity which is a principle of his nature, a radical condition of his existence, so much so that we could consider it a characteristic of the human species, and say: credulity is one of the attributes that distinguishes Man from the animals."

--Dr. Benjamin Verdo, Charlatanry and Charlatans in Medicine: A Psychological Study, 1867

Whoever would now imagine him the princely foundling, victimized naif, tortured wunderkind against crushing odds would've surely been as gulled by the mysterious teenager as so many in Nuremberg were for five years in the early 19th century, after he arrived suddenly to fascinate its locals, then deplete the charity of his several benefactors. Picayune, pretentiously paranoid persona, schizoid scammer, querulent, mythomaniac, pampered brat all probably described him accurately, yet this assessment is tangential to his characterization in the dreamily, alternately soothingly and shakingly speculative fairy tale that Herzog educed from the storied oddball's pseudobiographic lies. Here, Hauser's lifelong confinement in a cellar is concluded when a gruff stranger (Musäus) frees him, teaches him how to walk, leads him to Nuremberg, and abandons him. The inelegant innocent is housed first by one of his jailers (Prechtel), then by a kindly schoolmaster and philosopher (Ladengast) after a stint in an exploitative circus's sideshow. Thenceforth he strives to read, write, play music and comprehend the worlds within and beyond him, succored by his caretaker, local clergy (Patalas, Pilgrim), and a milord (Kroecher) whose custody of him is prompted by the intrigue that his charge inspires among townsfolk and high society alike, and which ends when his inscrutably bizarre behavior and provocatively peculiar perspectives embarrass his patron. As genteel characters, the entire supporting cast are fine foils for goggling Schleinstein, whose droll, piteous, exceptional creation of the frustrated aberrant conveys arduous articulation by his haltingly intense delivery. His age was well over twice Hauser's, but the autodidactic musician and painter proved a strikingly suitable lead, perhaps because the many ordeals that he suffered in his much longer life so often paralleled those that Hauser likely fabricated, fictionalized by Herzog in his discerningly, interchangeably intimate and observational style. Beautifully crafted and replete with allusions and auguries, never does this fiction moot nearly everyone's first, forever unanswered question: who was he?

Recommended for a double feature paired with The Marquise of O.

Escorts (A.K.A. High Class Call Girls)

Directed by Dan Reed

Produced by Dan Reed, Tom Costello

Starring Emily Banfield, Cookie Jane

No realm of commerce has been unaffected by online interaction; for the obsolescence of pimps and madams, and its suppled transactional dynamics, prostitution is no exception. Two tart trulls (Banfield, Jane) residing together with their cute dogs in one of London's richest districts command considerable compensation from a carefully selected clientele as fond of their personable ribaldry as their artificially augmented anatomy and lineaments. Obnoxiously likable and oversexed, they could be easily misappraised as mere dingbats, but their entrepreneurial acumen and ambitions would belie such a facile estimation. These cocottes receive trustworthy tricks, only accept cash, and leave very little to chance. Banfield narrates a crucial, collapsed relationship and addiction to cocaine spanning from her late teens through her mid-twenties, whence she rebounded into the relative comfort and security of pornographic and meretricious careers, while Jane's metier apparently attends her insatiable libido and aversion to conventionally respectable labor. Interviews with the latter bawd's parents disbosom their discomfort with their daughter's chosen profession, as well as a contrast between that quiet desperation of Albion's past and graying generations, and the histrionic, often hysterical effusions that have come to typify the urban British ethos over the past forty years. Some scenes are instructive for the uninitiated, depicting online discourse between the trollops and their potential and frequent customers, or a house call when they're administered injections of Botox. As Jane launches her own online agency whereby her circle of escorts can negotiate libidinous encounters, Banfield saves and seeks a permanent partner as her career winds down. Despite Chad Hobson's largely direful music, Reed's strictly observational portrait of these cyprians is usually as amusing as its subjects. It also instantiates how molls and johns alike are mutually exploited in their engagements, and explodes the delusion advanced by some feminists that empowerment neutralizes exploitation; here, technology manifestly conduces a harlot's market of which exploitation's immanent.

Eyewitness (1981)

Directed by Peter Yates

Written by Steve Tesich

Produced by Peter Yates, Kenneth Utt

Starring William Hurt, Sigourney Weaver, Christopher Plummer, James Woods, Steven Hill, Morgan Freeman, Pamela Reed, Kenneth McMillan, Irene Worth, Albert Paulsen, Keone Young, Chao Li Chi, Alice Drummond

Burdened by supernumerary character development, Yates's and Tesich's second coaction after Breaking Away doesn't quite compass its potential as a murder mystery or a romance. A janitor (Hurt) employed at a palatial office building reports the murder of a businessman (Chi) who'd leased an office therein to two cynical detectives (Hill, Freeman), who correctly suspect his maniacal buddy (Woods) of means, motive and opportunity. Their case is complicated by the unsophisticated custodian's incomplete disclosure -- recounted first to them, then to a fetching news reporter and chamber pianist (Weaver), who's enticed by the prospect of breaking a story that's closer to home than she imagined. Tesich's story is timely and absorbing, but his script's plagued by his zeal to humanize nearly every single character with at least one deepy personal, expository monologue or discourse -- all of which are delivered so well by Yates's eximious ensemble that one almost doesn't notice this superfluous sentiment. Singly fresh from Altered States and Alien, Hurt and Weaver effortlessly inhabit proper parts with charm and conviction, but their shortage of chemistry does nothing to make their amorous developments seem any more probable. Woods hyperactively betokens some of his best work to come as the volatile Vietnam vet who drives the plot. Most notable for its population of established and ascending stars, this one almost hits its mark, and almost satisfies.

Faults (2014)

Directed and written by Riley Stearns

Produced by Keith Calder, Jessica Calder, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Roxanne Benjamin, Chris Harding, Brian Joe

Starring Leland Orser, Mary Elizabeth Winstead, Chris Ellis, Beth Grant, Jon Gries, Lance Reddick

Few are so vulnerable or amenable than during a forlorn nadir, as that suffered by a disgraced expert (Orser) of cultic phenomena posterior to his career's collapse: divorced, indebted, indigent, homeless and sleeping as often as not in his godforsaken AMC Pacer, the whilom celebrity hawks a piffling hardback feebly redolent of his prior bestseller when hosting lectures of waning attendance worsened by his peckishly petty personality. After one such seminar, an aging suburban couple (Ellis, Grant) approach him to abduct, sequestrate and deprogram their daughter, an ardent cultist (Winstead). What first seems an opportunity to reverse his fortunes by settling a debt to his brutish, onetime manager (Gries) spirals suddenly into an uncontrollable nightmare: the infamous doctor's quietly beguiled as much by the resolve and allure of his kidnapped patient as her faith's intrigue, while her father's aggression intimates a paternal impropriety, destabilizing their apparent progress no less than a series of mystifying occurrences, all compounded by the pressuring presence of his creditor's dire, dapper deputy (Reddick), who duns the bedeviled psychotherapist with veiled threats. Optimally static shots and slow zooms constitute most of Stearns' first feature, which prepossesses at a leisurely pace wherein scarcely a penetrating, amusing or disconcerting moment's wasted. Orser's a seasoned character actor who deserves a lead now and again, and creates his shrewd, shallow, ruined pop psychologist at the brink of caricature, but pulls back for glimpses of insight and affirmations of his frailties and humanity. His exchanges with Winstead are as perfectly played as sharply scripted; clinician and subject gradually interchange, she leading by expounding her metaphysical convictions and aspirations, and emitting a sex appeal nearly imperceptible for its nicety. Most of the supporting players are as colorfully outstanding as costumes, sets and cars selected to lend this microproduction a fashion evocative of the early '80s. Gries is especially memorable as the creepily effeminate professional photographer of domestic portraits, whose squeaky-clean idiolect, replete with minced oaths, contrasts with his violent temperament. A cameo whereby A.J. Bowen uncharacteristically overplays an aggrieved relative who confronts Orser's fallen specialist at one of his pissant events should've been reshot entirely, and some humor during the picture's first fifteen minutes falls flat. Otherwise, the Texan photographer turned filmmaker adroitly juggles comedy and drama with dashes of arcana all scrupulously shot, and tautly cut by one Sarah Beth Shapiro. Ironically, Stearns lost his leading ladylove to the Anglosphere's greatest cult after Winstead divorced him in starkly hypergamous favor of a dimwitted, Scottish leading man, with whom she stridently signals her virtue to promote horrendous independent and studio productions to which she's now committed. That's a subject for another review or twelve; this penultimate picture in which her histrionic potential was tapped after transitioning to serious roles suggests what might've been, and potently portrays how privation of wealth, society and self-respect lays the mind supine to suggestion.

The Founder (2017)

Directed by John Lee Hancock

Written by Robert Siegel

Produced by Jeremy Renner, Don Handfield, Aaron Ryder, Michael Sledd, Parry Creedon, Glen Basner, Holly Brown, Alison Cohen, David Glasser, David S. Greathouse, William D. Johnson, Christos V. Konstantakopoulos, Karen Lunder, Bob Weinstein, Harvey Weinstein

Starring Michael Keaton, Nick Offerman, John Carroll Lynch, B.J. Novak, Laura Dern, Linda Cardellini, Kate Kneeland, Patrick Wilson, Justin Randell Brooke, Griff Furst, Wilbur Fitzgerald, David de Vries, Andrew Benator, Cara Mantella

"The definition of salesmanship is the gentle art of letting the customer have it your way."

--Ray Kroc

In his own words: "I was 52 years old. I had diabetes and incipient arthritis. I had lost my gall bladder and most of my thyroid gland in earlier campaigns, but I was convinced the best was ahead of me." In the mid-'50s, aging salesman Ray Kroc (Keaton) itinerated interstate, struggling with sporadic success to peddle Prince Castle's deluxe milkshake mixers to proprietors of drive-ins, whose sloppy refections and shoddy service courtesy of pretty, rollerskating carhops were insults added to every unsold injury. To satisfy a seemingly impossible order for eight such units in San Bernardino, he happened upon a modern miracle of a little eatery that prepared for lengthy queues cheap, savory, instantaneously prepared burgers, French fries and milkshakes by skilled, sanguine, sanitary staff indoors. A tour of this facility by its owners, designers and managers, Richard (Offerman) and Maurice (Lynch) McDonald, fascinates Kroc, as does their alacritous account over dinner of their career in the food service industry: thirty years of presentational and logistical trial and error developed with Mac's procedural and mechanical inventions, Dick's showmanship and their shared, reductive intent to eliminate troublesome conventions that resulted in a sedulously subtilized system that optimized both quality of service and product, and a quantity sufficient to satisfy every customer. The loquacious pitchman's consequently obsessed with a vision to franchise this local invention of fast food; after selling himself and their own business recontextualized as a boldly branded national chain to the circumspect siblings, he contracts with them as a franchiser to succeed where they failed to maintain the cibarious homogeneity and competence of extraneous outlets. Forays into new markets prove remunerative, but frustrating for that recurrent qualitative slide and their menus' regional drift, so the energetic Kroc replaces their managers with hungry, capable employees with whom he identifies, such as a hawker of Bibles (Benator) and a veteran of the Korean War (Franco Castan) who sells vacuum cleaners door to door. Despite his booming eastward growth, burgeoning eminence and obligation of his mortgaged house for capital, Kroc finds himself at a midwestern impasse and knee-deep in arrears for a deficit of revenue imputable to the restrictions of his contract, but a fortuitous encounter with financier Harry J. Sonneborn (Novak) introduces him to his shrewdest business partner, who convinces him to preveniently purchase prospective plots of his outlets and lease them to his franchisees via a corporation, to which he's eventually appointed by Kroc as its first president and CEO. By virtue of this M.O., the franchise's profits and expansion magnified twentyfold, but Kroc's failing marriage to his neglected wife (Dern), invited designs on the spouse (Cardellini) of a successful restaurateur and multiple franchisee (Wilson) and loggerheads with the brothers McDonald reveal the chatty oligopolist's amoral avaritia for limitless commerce.

Its intricate period detail and perfectly picked players sell Hancock's congenially conventional biopic, which is faithful enough to substantially portray a personage who's as much its antagonist as protagonist. Ever-squirrely Keaton mimics with slight amplification Kroc's accent and mannerisms, enacting the roguish devil with fidelity to his characteristic brio and glimpses of his elusive sensitivity. Everyone else serves as his foil with buttoned-down bearings true to this staid era. Warhorses of many quirkily mundane roles, Offerman and Lynch look and feel genuine as the ingenuously principled craftsmen who pioneered the revolutionary model arrogated by their franchiser, and Novak's icily mesmerizing as Sonneborn. Most fictive and biographic features are muddled by exposition and cutbacks, but thanks to Siegel's accessible dialogue, Hancock's demonstrative composition and Robert Frazen's measured editing, these are the picture's highlights: at a tennis court, Dick and Mac train their staff and gradually devise an ideal layout for their restaurant's production line with chalked, commensurate diagrams; Sonneborn enkindles in the audience a glimmer of the same excitement and relief that Kroc must've felt when elaborating on the potential of the chain's most significant single strategy; Kroc petitions synagogues, Shriners' Halls and Masonic Lodges for investment with an exhaustively rehearsed sales talk eulogizing familial values. Siegel's script often deviates from accuracy for dramatic purposes: neither was Kroc's divorce from his first wife so suddenly announced, nor his feuds with the McDonalds quite so wroth, and Cardellini seems sexier behind a piano than an organ when she first entrances her future husband. Ultimately, both Kroc and the McDonalds personify phases of postwar prosperity -- the former is an avatar of the tenacity and ambition that advanced the United States' extraordinary industries in the twentieth century, and the latter typical of so many innovators whose creations facilitated it. Bombs are still as American as apple pie.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Sometimes a Great Notion.

Happy People: A Year in the Taiga (2010)

Directed by Dmitry Vasyukov, Werner Herzog

Written by Dmitry Vasyukov, Werner and Rudolph Herzog

Produced by Vladimir Perepelkin, Christoph Fisser, Nick N. Raslan, Charlie Woebcken, Thomas Nickel, Robyn Klein, Werner Herzog, Yanko Damboulev, Timur Bekmambetov, Klaus Badelt

Starring Gennady Soloviev, Anatoly Blume, Anatoly Tarkovsky, Nikolay Nikiforovitch Siniaev, Werner Herzog

Not despite but for their travails do the isolated inhabitants of Siberia's frigid forests delight in rural survival. Vasyukov's televised documentary of four seasonal episodes is freshly compressed and concatenated, lushly (if excessively) scored by Klaus Badelt and narrated by Herzog with his usual phlegm as a feature uncovering a challenging, cheerful life of denizens from the village Bakhta in Russia's Turukhansky district, specifically those of rugged outdoorsmen (Soloviev, Blume, Siniaev, Tarkovsky) therefrom who handily eke out subsistence as trappers, hunters and fishers in the snowy, sylvan sprawl well beyond their little community's bourne. During this region's snowed spring, Soloviev cares compassionately for pups, curs, and seasoned hunting dogs alike of his doggery, fells a tree to split wood from it that'll later be fashioned into skis, contrives by carving and sets from two slender trees a deadfall of cunning design, perorates of his methodology and tools, denounces greedily unethical trappers, and rehearses his first onerous Siberian season forty years antecedent, which he scarcely survived. Blume conterminously shovels towering mounds of snow from the roof of one hut among several outlying a central shack within his designated territory (a configuration typical of all the trappers' winter dwellings), and collects firewood. While the vast ice floes constituting the surface of the Bakhta River (and Yenisei River of which it's a tributary) begin to flow north, children of the village skate about on thawing ice before their community first celebrates Maslenitsa by dancing and burning a straw, female effigy of winter, then Victory Day a week later, when wreaths are laid at the headstones of veterans who perished in WWII. One experienced Ket craftsman and an apprentice carve, widen, temper and pay with traditional methods canoes from tree trunks that are then boarded on exordial expeditions to train pups for future hunts, and with submerged toils catch fish, the choicest of which are smoked to be eaten later. Beasts and greenery emerge in profusion come summer, when fishing yields jumbo pike, and hunters collaborate to construct new central and collateral cabins while beset by swarms of mosquitoes, which are repelled by a topical concoction of tar distilled from birch bark and cut by immixture with fish oil. With the aforementioned wood split in the prior season, Soloviev and his son skillfully saw, carve, steep, flex and temper several pairs of skis. Driftwood collected upriver is towed to the shore, where Kets without occupational options chop and load it onto a truck's bed. Although this Yeniseian minority's elders struggle to preserve fading traditions, its community is mired in poverty, alcoholism, and resultant mischances. During comparatively warm days spanning twenty hours each, plentiful gardens are cultivated and planted, greenhouses mended, and chipmunks, sables and malleting, grinding, sifting humans all collect pine nuts from cones. Late in the season, an incumbent, regional candidate campaigns by cabotage, arriving at Bakhta's shore to tempt his largely indifferent constituency with a largesse of wheat and promises of reform before belting out a pop song with a trio of pretty female singers to entertain some congregated children and teenagers. Walls of stacked firewood, a massive harvest of fruits and vegetables planted months afore, and thousands of freshwater fish netted along the shoreline or lured by fire nocturnally to be leistered all portend autumn's advent. As the great Yenisei River rises for constant rainfall, and before its surface freezes, the hunters load their sleds and snowmobiles, dogs and provisions into canoes to convey them to their shanties; in high water, the rapids' fluxion often can't be countered by these boats' offboard motors, and exact for some such as Soloviev and his son manually arduous navigation. After they part, the elder trapper repairs damage inflicted by bears to one cabana, reposits there comestibles, shoots a woodcock and feeds its neck and feet to his dogs. While the rivers flow, pike are primarily caught to be fed to canines. Forbidding Tarkovsky (a junior cognate of Andrei) hunts and fishes with effectual craft, caches by suspension and elevation bread, grits, sugar and other aliments where neither bears nor mice can reach them, extols the simple pleasures of his lifestyle and sets mechanical slings to catch game. Soloviev expatiates on the ideal lineage, proper rearing, and necessity of dogs to any able hunter before one of his own predates a marten that he expels from a fallen, hollowed trunk. Winter finds the village's anonymous blacksmith forging a sharp shaft used to pierce the river's icy surface and enable more subaqueous fishing. During these most trying months of sustained yet stimulating slog, two events showcase the mettle of these woodsmen and their canine companions: fatigued after a day's labor, Blume retires to an ancillary hut to find its roof marred by a downed tree, which he chops and removes before clearing snow from his roof to repair it with immediate and laborious effort during his dwindling dusk; en route on his snowmobile to Bakhta where he'll sojourn with his family during its New Year's and Christmas festivities, he's chased over 90 miles by his dog to their home -- a feat as formidable for the animal's stamina as poignant for its loyalty. Vasyukov's subjects represent a rustic society's admirably hardy traditionalism, ably and objectively pictured here with fine photography and profoundly personal interviews that patefy an independence and integrity too uncommon in the developed world.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Encounters at the End of the World.

Hot Fuzz (2007)

Directed by Edgar Wright

Written by Edgar Wright, Simon Pegg

Produced by Ronaldo Vasconcellos, Tim Bevan, Eric Fellner, Nira Park, Karen Beever, Natascha Wharton

Starring Simon Pegg, Nick Frost, Jim Broadbent, Timothy Dalton, Paddy Considine, Rafe Spall, Olivia Colman, Kevin Eldon, Stuart Wilson, Edward Woodward, Anne Reid, Adam Buxton, Billie Whitelaw, Rory McCann, Karl Johnson, Eric Mason, Kenneth Cranham, David Threlfall, Lucy Punch, Paul Freeman, Ron Cook, Peter Wight, Julia Deakin, Trevor Nichols, Elizabeth Elvin, Bill Bailey, Tim Barlow, Lorraine Hilton, Patricia Franklin, Ben McKay, Alice Lowe, David Bradley, Maria Charles, Robert Popper, Joe Cornish, Chris Waitt, Stephen Merchant

Wright's comedies elicit overvaluation from the magnifying pathologies of approving British audiences, but they do meet a demand for nimble humor that Hollywood can no longer produce. Shaun of the Dead hardly met its hype, but this follow-up -- an uproarious lampoon of overcooked actioners by the likes of Tony Scott, John Woo, Michael Bay, Guy Ritchie, et al. -- merits its repute. From London, an accomplished, finical sergeant (Pegg) is transferred for his inconvenient superiority to a goofily idyllic village in Gloucestershire, where he's partnered with the oafish son (Frost) of his constabulary's chief (Broadbent). He chances instanter upon delinquency, deplorable dramatics, an overabundant arsenal, and a spate of murders that befall some of the locality's notables -- mistaken as mischances by his unskilled and complacent colleagues (Considine, Spall, Colman, Eldon, Johnson) -- just beneath a provincial veneer nurtured by its hospitable businessmen (Dalton, Wilson, Woodward, Whitelaw, Mason, Cranham, Freeman, Wight, Deakin, Nichols, Elvin). Pegg's again cast well to type as an authoritative straight man opposite clownish co-stars, funniest among whom are dopey Frost and lupine Dalton, who steals his every scene as a conspicuously sinister supermarketeer. That Welshman's fellow old hands play up their quaint parts with as much esprit as the director's usual collaborators; Whitelaw is meted a few droll scenes for her final appearance. Fans of Wright's circle will also enjoy snappy cameos by Martin Freeman, Steve Coogan and Bill Nighy as the overachieving officer's injudicious top brass. Most Anglophonic, contemporary cinematic comedies dole hors d'oeuvres for occasional laughs; here, Wright's and Pegg's buffet is crammed with frantically cut one-liners, sight gags, prefigurations and adversions intrinsic and extrinsic, many of which rely on the cunning casting of its older players. Featured clichés of the targeted genre include ostentatious rising pans and 360 shots, overzealous foley, digital blood, and dumb catchphrases. Whether they enjoy or abhor tasteless action pictures, this is recommended for whomever can stomach its multiple bloody homicides, especially Britons who need two hours of respite from metropolitan police farcically focused on trifling offenses, if only to divert public attention from their failures to curb violent crime.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Burn After Reading.

In Like Flint (1967)

Directed by Gordon Douglas, Robert 'Buzz' Henry, James Coburn

Written by Hal Fimberg

Produced by Saul David, Martin Fink

Starring James Coburn, Lee J. Cobb, Jean Hale, Andrew Duggan, Steve Ihnat, Anna Lee, Hanna Landy, Totty Ames, Thomas Hasson, Yvonne Craig, Mary Michael, Diane Bond, Jacqueline Ray, Herb Edelman, Robert 'Buzz' Henry, Henry Wills, Mary Meade

Never one to squander singular success, David sped this sequel to Our Man Flint into production to extend his property's lucre a year later, penned again by Fimberg with the same gratifying balance of action and comedy. Ruggedly rangy Coburn returns as enlightened, polymathic, coolly charismatic superspy Derek Flint, who braves federal soldiers, KGB agents, hostile environments and gorgeous ladies at a security complex of intelligence agency ZOWIE, on rooftops in Moscow, amid the rampant forestry and cascades of the Virgin Islands, in a cryogenic chamber, and aboard a space capsule in sublunary orbit to oppose a nefarious general (Ihnat), his presidential impostor (Duggan) and a cabal of distaff industrialists (Hale, Lee, Landy, Ames) plotting an artistic agendum to effectuate global female supremacy. One-liners, sight gags and gadgetry galore make this spy spoof a pinch more risible than its predecessor, dryly played with prowess by a game cast, and especially toothily indefatigable Coburn and Cobb as ZOWIE's defamed, bumblingly lovable chief. Directorial journeyman Douglas helmed this affair with deft disinterest; consequentially, Coburn and co-star/second unit director/stunt arranger/stuntman 'Buzz' Henry directed and performed plenty of its most exciting shots. This movie fits the bill for purely amusing adventure, but sends up institutional rigidity, women's liberation and the Cold War with far more dash and wit than that observed in most cinematic satires. Third- and fourth-wave feminists are likely to loathe Flint and his second outing without grasping that Fimberg was poking fun at both sides in their endless war of the sexes.

Recommended for a double feature paired with Our Man Flint, Casino Royale, or Batman: The Movie.

In the Name of My Daughter (2014)

Directed by André Téchiné

Written by Renée Le Roux, Jean-Charles Le Roux, André Téchiné, Cédric Anger

Produced by Olivier Delbosc, Marc Missonnier, Guillaume Canet, Christine De Jekel

Starring Guillaume Canet, Catherine Deneuve, Adèle Haenel, Jean Corso, Judith Chemla, Mauro Conte, Pascal Mercier, Tamara De Leener, Jean-Marie Tiercelin, Laetitia Rosier, Ali Af Shari, Hubert Rollet, Jean Vincentelli, Jean-Paul Sourty, Grégoire Taulère, Tanya Lopert, Paul Mercier

"Certain loyalty comes only through dependency."

--Richard Nixon, Leaders

If an account of criminal and juridical history constitutes spoilers, so be it. In mid-'70s Nice, widowed gaming proprietress Renée Le Roux (Deneuve) sustained fraud and silent threats by Calabrian mafiosi backing her covetous competitor, Jean-Dominique Fratoni (Corso). After refusing to appoint her underhanded lawyer Maurice Agnelet (Canet) as her gambling den's manager, he conspired with her criminal rival to unseat her by seducing her grasping, gaumless daughter Agnès (Haenel) before manipulating her to vote against her mother's reappointment as the casino's president. During the gaming house's liquidation, Agnelet either iced the junior Le Roux or lured her to her assassination, then assumed the 3M francs of their joint accounts that Fratoni paid her for her filial recreance. Despite the absence of her corpse, Agnelet was eventually convicted of her murder after three trials nearly thirty years later.

Technical excellence, unsurprisingly superlative enactments and a virtuous restraint elevate Téchiné's dramatization of this shameful affair above most of its kind. Like his womanizing, sleazily smarmy subject, Canet isn't at all obvious in his interchange of allurement and quiet menace. Brainless, bitchy, bovine Haenel (French cinema's face of Americanized, fourth-wave feminism) is usually awful in lubricious roles, but apt for the acquisitive, confiding, lovelorn, ultimately unsympathetic victim opposite Deneuve, who once again meets expectations as Téchiné's (and everyone else's) favorite leading lady with a perfectly poised, then mournful personation of her maternal crusader. Téchiné's style is more commonly cinematic here than in his early work, in which his floating and sweeping pans, and occasional zooms would've been unimaginable; they're as slick as Hervé de Luze's painstaking editing, which is essential to no few of the director's conceits. Floral hues pop brilliantly against verdancy and richly textured wood and stone before Julien Hirsch's lenses, which capture both the rural beauty of numerous landscapes and Lucullan interior detail of casino and courthouse alike. As credible as the cast, Olivier Radot's production design reflects an intricate but sensibly limited attention to period detail, manifest best in Pascaline Chavanne's crack costumery. Only two errors mar this otherwise premium production. Most of Benjamin Biolay's charming score (especially its peppy, neoclassical main theme) couldn't be more tonally incongruous. Téchiné was wise only to portray the major events of this case that were publicly confirmed, but his ruth for the faithless, frivolous heiress is unjust. Most contemporary French aren't prepared to accept that some victims earn their fate.

The Manhattan Project (1986)

Directed by Marshall Brickman

Written by Marshall Brickman, Thomas Baum

Produced by Marshall Brickman, Jennifer Ogden, Bruce McNall, Roger Paradiso

Starring Christopher Collet, John Lithgow, Jill Eikenberry, Cynthia Nixon, John Mahoney, Abraham Unger, JD Cullum, Manny Jacobs, Charles Fields, Eric Hsiao, Robert Sean Leonard, David Quinn, Geoffrey Nauffts, Trey Cummins, Fred Melamed

"When the bomb is detonated in the middle of a city, it is as though a small piece of the sun has been instantly created."

--Philip Morrison, 1945.12.6

Some opportunities are more obvious than others, swelled as their salience seems for pique, pressure and perspective. An upcoming annual science fair in his native New York and the courtship of his mother (Eikenberry) by a nuclear physicist (Lithgow) inspire a mischievous teen genius (Collet) to pilfer particularly potent plutonium from a newly-erected laboratory where the elder egghead's employed as a supervisor. Late in the Cold War, what could be a more relevant and impressive project than a personal nuclear bomb? Woody Allen's most conventionally inventive collaborator bravely bares both his flair and failings in this underrated science fiction, which compulsively supposes a potentially explosive confluence of adolescent recklessness and the intellectual allure of dangerous technologies. Brickman's direction and script are equally fine, farced with witty dialogue and a satisfying romance between Collet's whiz kid and his co-conspirator/emergent girlfriend (Nixon). Withal, a couple of Brickman's and Baum's best scenes are all but speechless, such as their protagonist's infiltration of the laboratory and abstraction of radioactive specks suspended in gelled scintillant therein, executed with two Frisbees, an RC toy truck, and a catoptric array emplaced to direct the facility's powerful laser beam. His bomb's construction during a mandatory montage is fascinating enough to overcome the implausibility of its safety, and with quips and action aplenty, these proceedings are swiftly paced and tonally balanced. When a joint team of federal agents and military officials led by a suspicious Lieutenant Colonel (Mahoney) investigate Collet's homemade doomsday device, that playful parity of humor and suspense is sustained surprisingly well to a slightly sloppy but charming conclusion. The main theme of Philippe Sarde's jaunty score is derived equally from his autoplagiarized love theme in Le choc and The First Noel, and subjected to numerous, cleverly melodic variations. For none of its few flaws did this ambitious feature deserve its critical and commercial failure.

Recommended for a double feature paired with WarGames.

Omar (2013)

Written and directed by Hany Abu-Assad

Produced by Hany Abu-Assad, David Gerson, Waleed Zuaiter, Joana Zuaiter, Abbas F. Eddy Zuaiter, Ahmad F. Zuaiter, Farouq A. Zuaiter, Waleed Al-Ghafari, Zahi Khouri, Suhail A. Sikhtian, Baher Agbariya

Starring Adam Bakri, Leem Lubany, Waleed Zuaiter, Samer Bisharat, Eyad Hourani, Ramzi Maqdisi

"To do injustice is more disgraceful than to suffer it."

--Plato, Gorgias

On the high road where he steps lightly in concern of its political and religious facets to evade complications and assure the commercial and distributive viability of his pictures, Abu-Assad's cannily unveiled the humanity of the Palestinian struggle with Paradise Now, then this superior crime drama that demonstrates how dretchingly personal and martial imperatives can snarl. A baker (Bakri) regularly hazards gunfire by the IDF's snipers and their patrols' persecution to scale a border wall that segregates Palestinians from Israeli settlers in the West Bank, where he visits his militant friends (Hourani, Bisharat) and one's lovely sister (Lubany) with whom he's smitten. Jailed and railroaded for nicking a car as transportation to a military outpost where one of his buddies assassinates a soldier, he's taught by a gauntlet of incarceration, torture, betrayal, heartbreak, and the legerdemain by an agent (Zuaiter) of Shin Bet -- who offers him highly conditional freedom in exchange for his comrades -- that one of his own is as perfidious as their oppressors. Corporate perpetrators of stodgy, overproduced fare could learn something from Abu-Assad's economical feature, which is adeptly plotted, performed, shot and cut with lavish twists, a gripping pair of pursuits, one deeply moving, ruined romance, and an unforgettable conclusion, without a moment of hokum. It's also one of but a handful of movies to relate that for aggrieved Arabs and Jewish occupiers alike who participate in the everlasting conflict provoked and perpetuated by the world's most prosperous, parasitic, hypocritical, fraudulent and remorselessly abusive apartheid state, there is no contrition, no reprieve, no guarantee of anything, save death and reprisal.

One of Us (2017)

Directed by Heidi Ewing, Rachel Grady

Produced by Heidi Ewing, Rachel Grady, Alex Takats, Liz F. Mason

Starring Etty, Ari Hershkowitz, Luzer Twersky, Chani Getter, Yosef Rapaport

Ostracism and contingent harassment await whoever dares to leave Brooklyn's Hasidic community, as explicitly related by a trio of such deserters in extensive interviews and observations. Pseudonymous Etty struggles to retain custody of her seven children after forsaking a routinely ill-arranged marriage to an abusive and unloving husband, and finds some comfort in a support group organized for therapeutic congregation of other whilom Hasidim. Still reeling from the harrowing humiliation of his public pedication and shunned by former friends, Hershkowitz revels in newfound freedom before and after his recovery from an addiction to cocaine. Aspiring actor Twersky ekes emolument as a driver for Uber where he's resettled in Los Angeles, residing in a parked RV and willingly typecast in Hasidic roles to assert his individuality and distance himself from the ex-wife and offspring he's left behind. Ewing's and Grady's prior feature on religious extremists was the amusive, hyperbolically marketed Jesus Camp, which presented a laughable evangelical summer camp and its silly, sanctimonious attendees as unduly significant, and was strategically edited either by the filmmakers or their co-producers to nearly omit extensive evidence of their subjects' unrequited fealty to Israel. Slickly shot, scored, cut and titled, this dour documentary finds them in better form, exploring how the cultish Hasidic tribe sustains its traditions, security and continuity by means both kind and cruel, commanding private schools, ambulances and a police force to support one another and enforce their precepts while domiciled in Brooklyn's best subsidized housing. Both the mistreatment they've suffered and curiosity concerning the outside world fortify the resolve of these three anathemas, who pine for past fellowship while basking in the United States' secular liberty. None of them were at all prepared for life beyond Brooklyn, all speaking English second to Yiddish, nearly innumerate for the calculatedly selective deficiencies of their education, and as ignorant of the Internet for its proscription -- a bitter irony in light of the Ashkenazic affinities for mathematics and online entrepreneurialism. Geller (who organizes the aforementioned support group) expounds how the uncompromising stringency of Hasidic piety and insularity is as much a reaction to the sect's decimation during the Holocaust as devoted abidance by its tenets. Reactions of Hasidim to those who've abandoned their fold vary depending on their circumstances. Etty's persistently terrorized by her husband and his family, and threatened with the loss of her parity because nomistic Hasidim can collectively afford the lawyers she can't. All but isolated for his abandonment, Hershkowitz is advised by one of his community's friendly yet firm elders (Rapaport), who voices compunction for his adversity and disapproval that it wasn't redressed, but also admonition for his relatively liberal lifestyle and existential and theological inquisitiveness. Those few acquaintances from whom Twersky isn't estranged only treat him with stilted civility. Outside the Islamic world, tergiversation is seldom met with such alienation, but these are not apostates: notwithstanding Hershkowitz's doubts of divinity, they're all practicing Jews more dedicated to dogma than most. This picture's portrayal of Hasidim discloses of them qualities seemingly paradoxic: they're at once scholarly and stagnant, loyal yet parasitic, neurotically fanatical in their crusade to resist modern, godless progress in a manner less extreme but far more aggressively adamant than that of the Amish. Ewing, Grady and their interviewees impart that this enclave needs to change -- not to neglect or degrade their customs or consecration, nor to intromit outsiders or their culture, but to mend and forfend ingrained cycles of domestic and institutional abuse. If a stable society requires accountability, then a fortiori is it indispensable for any so closed.

The Panic in Needle Park (1971)

Directed by Jerry Schatzberg

Written by James Mills, John Gregory Dunne, Joan Didion

Produced by Dominick Dunne, Roger M. Rothstein

Starring Kitty Winn, Al Pacino, Alan Vint, Richard Bright, Kiel Martin, Michael McClanathan, Warren Finnerty, Marcia Jean Kurtz, Raul Julia