2024/12/30

If I'd superlatives that adequately describe the excellence of these movies, I wouldn't need to posit that not one wooden chair yet fabricated has ever struck a back with the impact that these imparted to me. Would that I had seen most of them sooner!

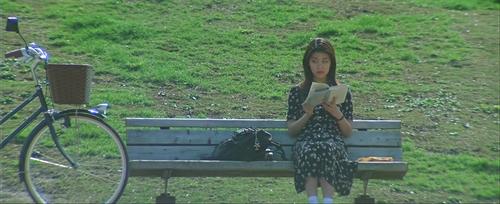

Beauty and charm abound even in Shunji Iwai's fluffiest flicks, as this vehicle for gorgeous pop singer and actress Takako Matsu, who cutely creates a diffident young lady from northern Hokkaido who relocates to Tokyo with some difficulty, and enrolls at a university there to meet friendly strangers, attend a screening of a silly old chambara, and reconnect with the handsome classmate (Seiichi Tanabe) with whom she's enamored. Gorgeously lensed by DP Noboru Shinoda, Iwai's fleeting, featherweight feature is worth watching for a few gentle laughs and the pulchritude of its photography and cast. Accomplished kabuki performers Matsumoto Hakuo II and Matsumoto Koshiro X -- Matsu's respective father and brother -- appear as such in introductory cameos.

Following his mother's tragic death during Showa wartime, the son (Soma Santoki) of a wealthy industrialist (Takuya Kimura) is relocated with his aunt/stepmother (Yoshino Kimura) to her rural home, where his exploration of a tower constructed by his enatic great uncle (Shohei Hino) during the Meiji era leads him into an otherwordly crossroads for the dead and living, where time and space may be ranged through doors and the fabric of reality seems unusually mutable. Produced at enormous expense over seven years, Miyazaki's thematically abundant, quasi-autobiographical, probable swan song is no less touching or imaginative than most of his best pictures, and doesn't bother to hold its viewers' hands through many dizzying transitions and scenarios. Inter alia, Ghibli's co-founder here posits that creation and destruction are often antipodal aspects of the same phenomena -- an observation expressive of his insistence on balance and harmony in seemingly chaotic worlds.

Six remakes of Oriol Paulo's The Invisible Guest have been produced thus far; this glossy, wintry Korean rework all but surpasses the original with superior performances, slicker direction, and some twists that never occurred to Paulo. Upon his release from police custody, an IT firm's CEO (Ji-sub So) recounts to his seasoned legal counsel (Yunjin Kim) how he was discovered by the police in a locked hotel suite with his erstwhile, murdered mistress (popstar Nana) -- a story that she refutes in connection to a disappearance involving he and the deceased. As in Guest, a new revelatory twist every 10 to 15 minutes upends the cunningly crafted and adapted plot, as well as one's perception of its feloniously unreliable narrator, played with minatory nuance by veteran prettyboy So opposite Kim at her most frigidly incisive; her temperament befits such a snowy setting.

Aboard a paddle steamer down the Nile during an Egyptian honeymoon with her husband (Simon MacCorkindale), the callous, beautiful, Anglo-American heiress (Lois Chiles) of a regal landed estate and vast fortune is murdered at close range. Unfortunately for holidaying Belgian sleuth Hercule Poirot (Peter Ustinov) and a retired British colonel (David Niven) who he befriended years before, nearly every other passenger aboard (Mia Farrow, Bette Davis, Maggie Smith, Angela Lansbury, George Kennedy, Jack Warden, Olivia Hussey, Jon Finch, Jane Birkin) had means, motive, and opportunity to commit the crime. Worse still, the culprit at large isn't averse to sequent killings to tie up loose ends -- and the rotund detective may be one of his or her targets. Superb follow-up to the enormously successful Murder on the Orient Express finds Ustinov perfectly cast in his first of six outings as Poirot (after Albert Finney refused to submit to more uncomfortable prosthetics), and spars well with another phenomenally assembled cast in this fairly faithful adaptation of Christie's classic, in which her trademark black humor and blacker cunning are smartly helmed by genre vet John Guillermin, furnished with superb interwar detail by costume designer Anthony Powell and production designer Peter Murton, and afforded authenticity in striking locations of Egyptian ruins. It's as indispensable for enthusiasts of cinematic Christie as for fans of anybody in its sublime cast.

A concussion leaves a flaky, self-absorbed bookworm (Tomohiro Kaku) suggestible to the notion that cute, clumsy, crushing Hana (Anne Suzuki) is the girlfriend who's he's amnestically forgotten, and that her elegant best friend Alice (Yu Aoi) is an embittered ex-girlfriend who he jilted. Meanwhile, ballerina Alice struggles to cope with her parents' divorce and find a suitable gig after she's scouted on the street by a talent agency. Iwai ingeniously realizes more great visual, dramaturgic, and comedic ideas than one will observe in most movies in any few scenes of his bittersweet comedy, which emphasizes the necessity of friendship and beauty during the turbulence of adolescence. For their final collaboration, Noboru Shinoda indued an often hazy vividity to his photography that's at least as resplendent as its pretty leads.

In postwar Tokyo, a widowed professor (Chishu Ryu) urges his doting, devoted daughter (Setsuko Hara) to marry and start a family, but she's content to cook, clean, and mend for her father. Only by scheme and sacrifice can he prompt her to move on with her life. Ozu's masterwork is perfectly played, statically shot with painstaking care, and arguably his best picture, which established the formula on which many of his subsequent works were predicated. Halfwitted occupational censors couldn't penetrate his dramatic vision, which subtly contrasts traditional culture with crass modernity while demonstrating how ordinary Japanese reconciled past conventions with present circumstances. Hara co-starred in six and Ryu in all of Ozu's features during his last fourteen years, none of which are more stirring than this exposure of family as a social expression of cyclic life.

No particular conflict intrudes upon the dissatisfying urban life of an exhausted, unfulfilled student (Tae-ri Kim) who fails a crucial exam, abandons her noncommittal boyfriend, and repairs to her childhood home in an agricultural region known for its rice and apples. Lessons and recipes imparted by her widowed, absent mother (So-ri Moon) since childhood provide sustenance and a means to reconnect with friends, a local bank's pert teller (Ki-joo Jin) and a phlegmatic famer (Jun-yeol Ryu) with whom she's smitten. Elegant direction by feminist auteur Soon-rye Yim is notable for its slowly drifting shots, mouthwateringly cibarious close-ups, and occasionally surprising conceits by which filial memories segue in juxtaposition with contemporary activity. The humble gentility of her drama (adapted from Daisuke Igarashi's popular, eponymous manga) illustrates its burden: processed foods and urban artifice can't nourish everyone.

On the second anniversary of an amateur mountaineer's untimely death, his fiancée (the late Miho Nakayama) pens a letter addressed to him at his adolescent home, and is surprised to receive an answer from his whilom classmate, a sweet, flaky librarian (also Nakayama) who shares his name and her likeness. Bereavement recedes and romance blooms anew between she and the boldly fervent glassmith (Etsushi Toyokawa) who adores her, conduced by her correspondence and trips to her pen pal's and lost love's hometown of Otaru, Hokkaido, and the mountain where he died. Iwai's poignant, hibernal, bittersweet, funny first feature isn't just one of the best pictures of the '90s; it's also the movie that finally effected reception to Japanese cultural output in South Korea, where it's still screened on occasional theatrical revivals. Even at his most sentimentally accessible, Iwai still challenges with a paradoxic dynamic that contrasts two personalities and their perspectives by embodying them as the same lovely actress. Great perfomances from his photogenic cast and beautifully hazy photography courtesy of his recurrent cinematographer Noboru Shinoda only substantiate Iwai's mastery as a director and editor who came to prominence by one of his most inspired efforts.

A rural schoolteacher (Gao Enman) takes a monthly leave of absence to care for his moribund mother; his substitute is a bright but inexperienced girl (Minzhi Wei) of 13 who's promised payment and a bonus if she can reliably educate and retain her rambunctious charges. When the class clown (Huike Zhang) drops out to find work in Zhangjiakou, his pertinacious pedagogue follows him to the little city and struggles with obstacles and errors to reclaim his attendance. Akin to his The Story of Qiu Ju, Yimou Zhang's most pastoral picture concluded his best decade by realistically depicting poverty in rustic locations populated with amateur actors, whose natural enactments were educed by instruction to play themselves. Idiotically politicized animadversions from kosher media outlets couldn't rightly besmirch Zhang or his moving, effective call for improved educational funding in benighted ruralities. For those who ignore its message, it's still a fine small drama and a compelling glimpse of agrestic China.

Weary of the world and himself, an accomplished Anglo-American journalist (Jack Nicholson) reaches his breaking point in Saharan Africa while agonizing to shoot footage to complete a televised documentary regarding a despot who's quashing civil unrest. Opportunity knocks from a neighboring hotel room when an acquaintance (Charles Mulvehill) succumbs to a heart attack, whereupon the disaffected newsman exchanges their identities to escape his occupation, unfaithful wife (Jenny Runacre), and existential dissatisfaction. Upon rendezvous with professional associates in Germany and Spain, he realizes his assumption of an arms dealer's identity before meeting in Gaudí's Palau Güell a pretty architectural student (Maria Schneider) who's excited by the danger and mystery that her new lover is trying to escape. Ipseity is yoked to destiny in most of Antonioni's pictures, and in this supremely slow, superbly shot classic, he denudes the nature of anomie as an exhaustion of spirit, underplayed by Nicholson (as an antipode to his manic rebellion in contemporaneous Cuckoo's Nest) opposite Schneider at her ruminatively vulnerable best. In no desert of Africa or Iberia may one witness a desolation comparable to that of the vacant soul.

Cozened, shot, and left for dead on Alcatraz Island by his loathsome partner (John Vernon) and wife (Sharon Acker), one leathertough career criminal (Lee Marvin) quickly adapts to his understanding that life won't improve until he wrests what's rightfully his from his betrayer's Angelean crime syndicate, but vengeance is much more readily fulfilled than money withdrawn from an organization that's deliberately decentralized. His first stateside movie is John Boorman's very best, one of the first true classics of New Hollywood and a quasi-surrealistic depiction of efficient organized crime as a reflection and microcosm of an evermore automated, atomized, inhuman modern society. Marvin looms larger than life through dreamy, anachronous, alternately reflective and violent scenes in a production that eschewed convention, and was secured by his clout.

© 2024 Robert Buchanan