2024/12/28

If I'd thought to compile this list last year, I would've reviewed many more interesting pictures: Birds Without Names, Romance Doll, From Miyamoto to You, and some other stuff that doesn't co-star Yu Aoi, I guess. Anyway, these aren't bad movies -- all of them are in some way quite fine, even excellent -- but for whichever flaws, they just don't make the grade. Usually, that's the fault of screenwriters and/or producers. Some of these are actually recommended, with heavily qualified reservations. Others are deeply disappointing, like a vision hosted by an evil Christmas angel who reveals in a flashback how the chair broken over the back of somebody's stupid mom was actually made of balsa wood, or by Fisher-Price. Proceed and select with caution.

This adaptation of Yoshiie Goda's eponymous manga is probably the weakest of Kore-eda's features, but it didn't need to be; had the hypersensitive auteur excised its contrived tragedy and pointlessly despondent conclusion, it might've sufficed as prettily inspired fluff. Alas, a sex doll (Doona Bae) is destined for disposal after coming to life and experiencing love, heartbreak, and home video as an employee of a rental outlet, and reveling in the tensions and ambiences that so many humans take for granted. Kore-eda sought to explore loneliness as a theme, but pretty girls need never be lonely, be they of flesh or vinyl. Ultimately, this is an unfortunate waste of a good cast headed by one of South Korea's most exciting actresses, who creates a wholly believable ingenue -- but to what end?

=]=:< <"Remember in Crocodile Dundee when Crocodile Dundee stabbed that crocodile in the brain with his knife because he just emerged to say hello? That was only slightly more needlessly cruel than what happens in this movie. People think Kore-eda's some kinda gentle humanist like Ozu or Bresson or whoever, but it's not true. Remember what he did to that cute little girl in Nobody Knows? The man is sick. Sick."

Those whose bodes are inhabited by extraterrestrials (Ryuhei Matsuda, Mahiro Takasugi, Yuri Tsunematsu) who are visiting Earth to study humans in advance of a global invasion are already dead, and victims of their psychic practice to abstract emotions and concepts from minds suffer horribly for their sudden absence. Tomohiro Maekawa's stage play and novel Strolling Invaders was an ideal selection for treatment by Kurosawa (a vocal admirer of Don Siegel's and Philip Kaufman's efforts), but the auteur's slow pace is here misplaced, and motivations of certain characters -- as a freelance journalist (Hiroki Hasegawa) who abets the aliens -- are inexplicable. Despite surpassing performances from a choice cast -- esp. those of leading lady Masami Nagasawa as the wife of Matsuda's former self and Kurosawa's long-favored Atsuko Maeda in two quietly chilling scenes -- this is one of very few movies for which his critics' (usu. senseless) accusations of decadent tedium apply. Drably graded, uncharacteristically flat photography of DP Akiko Ashizawa (who's lensed several attractive movies helmed by Kurosawa) hardly mitigates this dullness. Other frequent collaborators (Masahiro Higashide, Kyoko Koizumi) of the director appear in small, moving cameos.

In self-defense, a half-Apache horsebreaker (Charles Bronson) shoots dead the sheriff who nearly murdered him; in retaliation, a posse (Richard Basehart, James Whitmore, Simon Oakland, Ralph Waite, Richard Jordan, Victor French, William Watson, Roddy McMillan, Paul Young, Lee Patterson, Peter Dyneley) led by the whilom Confederate Captain (Jack Palance) who recruited them pursue him across rugged wasteland, then instigate his revenge when some among them gangrape his wife (Sonia Rangan) and torch an abandoned village of wickiups. His knack for action, desert panoramas, and talented actors can't preserve Michael Winner's unsparing western from the flaws of its screenplay by his continual collaborator Gerald Wilson. White depredations are credibly depicted, but both justified and condemned with absurdly anachronistic language that only insinuates retaliatory sentiments without mentioning how and why the Apache were feared and reviled by white settlers and other red tribes. Beefy Bronson's a nearly perfect pick as the taciturn tracker, gunslinger, and horseman; alas, Palance, Basehart, and Jordan are squandered in roles that don't invoke their strengths. If its dialogue had been halved, and thematic focus directed to vengeance rather than the perpetuation of iniquity, this might be a good movie.

=]=:< <"Eww, the desert again? Hell, no. What is it with everyone and deserts? Get outta there! They can't support life."

Prefixture of Worst to its title would better describe many vocal deliberations of this teledrama, in which a sexagenarian judge (George C. Scott) opposes the intention of his aimless, accidentally pregnant daughter (Melissa Gilbert) to abort, until he discovers that his second wife (Jacqueline Bisset) is also expectant, and ready for motherhood. Judith Parker's propagandistic, admittedly provocative screenplay addresses some facets of abortional controversy and certainly the conflict experienced by older and indecisive pending mothers, but neither the obligations that contraceptive availability imply, nor the selfish frivolity of abortion to accommodate professional or academic ambitions. Her dialogue's natheless naturalistic and delivered well by its leads; irksome, forever frumpy Gilbert tolerably plays an irresponsible student, Scott's unsurprisingly impressive in alternating rumination and obstinacy, but Bisset verbalizes her pianist's frustration and indecision with a rare and vivid verisimility, particularly in a monologue during the third act. In the Anglosphere, propaganda of this subtlety is all but a lost art.

=]=:< <"For alligators and crocodiles, the debate concerning abortion has a very different complexion; specifically: white meat or dark meat? Ha ha ha ha! Seriously, though, what's left of those fetuses and babies that those Jewish sickos dump in our swamps and ponds after they're done with them are deeeee-licious! Yum."

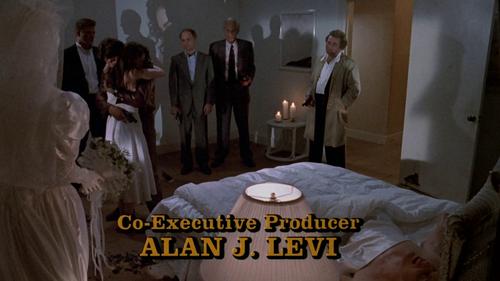

A beautiful bride (Joanna Going) has been kidnapped by a lunatic, and the bumbling uncle (Peter Falk) of her husband (Thomas Calabro) is more likely than anyone to locate her before she becomes the subject of a murder-suicide. Here's an episode that failed interestingly by deviating from its series' usual formula, largely because everyone who isn't Columbo is yattering inane exposition for the audience -- esp. drop-dead gorgeous Going, who explicates every detail of her efforts to escape because televisory producers can't tolerate a speechless minute or three. Audiences may be pleased with effective histrionism from some notable character actors (Daniel Davis, Donald Moffat, David Byrd, etc.), but this ill-concieved imitation of popular, conterminous, cinematic crime thrillers concerning serial killers (Manhunter, Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer, The Silence of the Lambs, Kalifornia) falls very flat. On the other hand, a morbid still-shot behind its end credits is hilarious.

His last few pictures are especially maladroit, proving that most of Stanley Kramer's successes resulted from his technical competence and the backing of studios willing to amplify his agitprop. However, none are as ham-fisted as this attempt to ride the coattails of popular, contemporaneous spy thrillers (Three Days of the Condor, The Parallax View, silly Marathon Man), a condign commercial and critical flop. With minimal explanation, a Vietnam vet (Gene Hackman) imprisoned for murdering the ex-husband of his wife (frumpily bewigged Candice Bergen) is interviewed by governmental spooks (Richard Widmark, Edward Albert, Eli Wallach) who oversee his early release, generous bankroll, and domiciliation in Costa Rica where he's reunited with his spouse in exchange for the assassination of an unfamiliar notable, which he stupidly refuses to commit. Adam Kennedy's screenplay (based on his popular novel) is skillfully plotted but frequently absurd, and its ambiguities are eventually tiresome well into a leaden second act. Despite its shortfall of suspense, Kramer's bomb is admittedly shot as well as it's acted. Opposite a fine selection of character actors, Hackman is riveting and wholly believable in the lead -- a doubly impressive feat considering that he was as baffled by his idiotic character and the movie itself as most others who saw it.

=]=:< <"Wow, that freeze-frame climax is the stuff of TV movies. Kramer has the kind of prestige that only ethnonepotism or loads of cash can buy. Spielberg can act like he's hot shit, but you ever notice how nobody except a shrinking little demographic of old leftards actually watches his movies? Expiration date for his crap was sometime in 1980, I think. Gay."

Denis Villeneuve screened the magnitude but neither the verbal and conceptual complexity nor ethos of Frank Herbert's epochal science fiction, so his bloated blockbuster deserves only an enumerative appraisement:

Imagine a filmic Dune produced and directed by those possessing brains, spines, and Herbert's unadulterated vision. Mayhap we need only wait until it enters the public domain in 2081.

=]=:< <"Chalamet's face is so stupid that I wouldn't even condescend to chew it off his scrawny head. Yick! That's not a hero; that's some twink who's addicted to god knows what, and to whom gay men turn up their noses. Disgusting. There's nothing for me here; the desert is a hellhole. Pass."

True love between an entrepreneur (Nanako Matsushima) and the potter (Seung-heon Song) to whom she's engaged endures after she's murdered, but she can only warn him of imminent danger with the relief of a frauduent yet genuinely ectoclairaudient medium (Kirin Kiki) who can hear her. Tearjerking, gender-swapped remake of the hit supernatural romance is sweet, sentimental, and cheesily melodramatic, though not much more so than its American predecessor from a score before. Its beautiful leads are more charming than Swayze and Moore, but they can't quite offset their glossy production's lack of distinction, which isn't helped by some bad exterior photography, middling to terrible CG derivative of the original's, or a particularly lightweight recording of Unchained Melody. Substituted for hideous Whoopi Goldberg, Kiki is the movie's best asset, and hilariously steals most of her few scenes. Less prefatory romance, much more of Kiki, and the subtle Japanese approach to matters spiritual would've helped, if not saved this from failure.

Sumptuously staged, overdramatic, ineluctable remake of Kobayashi's tragic chambara from nearly a semicentury prior finds kabuki thespian Ebizo Ichikawa XI in Tatsuya Nakadai's lightly ham-padded sandals as that aging ronin who visits a prospering clan to request of its daimyo's senior counselor (Koji Yakusho) the right to commit ritual suicide, but doesn't disclose his vengeful primary purpose until all are assembled in their castle's courtyard. Well aware that everybody and his brother's seen the severe, almost clinically composed classic, Takashi Miike wisely opted for more motion at less distance, and his supervision of a picture has seldom been executed with such immaculate deliberation. For a hobbled, more sympathetic recharacterization of Rentaro Mikuni's regal, forbidding officer, Yakusho affords a dram of depth and humanity to what was in Kobayashi's flick a simpler part. His delivery is authentic and the camera adores him, but unlike Nakadai, Ichikawa simply can't reach his character's dramatic heights without leaping over the top -- and those who'd dismiss a negative comparison with an onscreen icon should know that his acceptance of the role is an invitation for such animadversion. Action and drama alike are superbly shot by Miike's winning, experienced eye, but it's nearly to naught for a climactic, unbearably desipient deviation from Yasuhiko Takiguchi's novel and Shinobu Hashimoto's screenplay introduced by screenwriters Yasuhiko Takiguchi and Kikumi Yamagishi. Notwithstanding its few, flagrant flaws, one can't deny the quality of this production, or readily forget its chillingly serene conclusion.

Sweeping liberties, brilliant color and clarity courtesy of DP Jack Asher, and some great players distinguish Hammer's goofy, glossy dramatization of Doyle's oft-filmed novel, wherein Cushing brings his intimate knowledge of the detective to bear as perhaps the most peckishly precise Holmes yet filmed. A penultimate Baskerville expires mysteriously on the moor circumferent of his estate, which is entailed to a handsome young heir (Christopher Lee). The deceased's doctor (Francis de Wolff) tasks Holmes (Cushing) and Dr. Watson (André Morell) with an investigation of his friend's and client's death, and his heritor's security, but neither come easily nor clearly. Typically lurid silliness and Italian sexpot and future peeress Marla Landi's hammy turn as a love interest (made up with purple lipstick, no less) don't quite overshadow Cushing's and Morell's performances as an exemplary Holmes and Watson -- two of few elements faithful to the novel. Holmesian purists hate it, Hammer fans love it, and cinephiles are usually ambivalent for admiration of its technical quality and embarrassment for its schlockiest indulgences. Yes, the dog is very big.

A musicologist (Anthony Perkins) was accidentally responsible for the fire that killed his academically preeminent father and partially disfigured his sister's face, after which he's hospitalized in a psychatric ward for psychosomatic blindness symptomatic of his remorse. Upon his discharge, the still-sandblind scholar's relations with his sibling (Julie Harris) and fiancée (Joan Hackett) are strained for his acrimony and paranoia waxing for inexplicably suspicious events, as well as a shadowy, whispering, menacing figure that must be a figment of his inchoate schizophrenia....right? Few were so suited to his stuffy, suspicious lead part as slim, squirrelly Perkins, but solid performances from he, Harris, and Hackett can't overcome Curtis Harrington's perfunctory direction of a screenplay adapted by Henry Farrell of his popular, eponymous novel. Too bad: Farrell's story is as paranoiacally engrossing as any of his other best works (What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? or Such a Gorgeous Kid Like Me). Rightly lambasted by critics for its tedium, this is nonetheless required viewing for Perkins's fans.

One slight, admiring documentary celebrates the short life and shorter career of the gifted character actor, whose small filmography of classics have secured his permanent remembrance. Interviews with his brother Steve, co-stars (Meryl Streep, Al Pacino, Gene Hackman, Robert De Niro, John Savage), directors (Israel Horovitz, Francis Ford Coppola, Sidney Lumet), and prominent admirers (Richard Dreyfuss, Steve Buscemi, Sam Rockwell, Philip Seymour Hoffman, Olympia Dukakis, Carol Kane) delineate the histrion who specialized in the personation of sensitive losers, but scarcely outline the man. It's too fluffily produced, but an otherwise adequate tribute to a figure whose place in the annals of New Hollywood is at least as assured as those who survived him by decades.

Like many other American dramas, David Gordon Green's adaptation of Larry Brown's novel teeters between social realism and genre pulp, but its capable cast and Green's steady oversight largely salvage it from both the filmmaker's and novelist's most lurid indulgences. An ambitious teenager (Tye Sheridan) of an impoverished family joins sylvan laborers organized and managed by a tough, temperamental, goodhearted ex-convict (Nicolas Cage) whose incessant diet of booze and cigarettes unreliably checks his outbursts. Neither are prepared to cope with the boy's perverse, parasitic, abusively alcoholic father (Gary Poulter), who's at best an burden to his kin, and at worst a rapist and murderer when the mood strikes him. Oft-bathetic bloodshed that's as ably choreographed as shot doesn't always mesh credibly with the sober mood of life at the bottom, but this is worth seeing for Cage at his wonky best and Poulter, a local vagrant hired by Green who unexpectedly breathed powerfully vicious vacuity to the elderly reprobate just months before his death. The talent assembled by Green outshines the faults of his picture, which pulls no punches.

=]=:< <"Evil, drunk old dad wasn't eaten by a wild animal in the movie or in real life. Don't care."

Poe's unfinished short story The Light-House faintly influenced Robert Eggers's exquisitely crafted yet ludicrously overestimated period drama, in which a a lighthouse's inexperienced junior keeper (Robert Pattinson) is relegated to menial drudgery under the command of a gruff old salt (Willem Dafoe), who obsessively tends its lantern room in the buff. There's no rightful complaint to be voiced or typed regarding Eggers's craftsmanship, which is meticulously staged, framed, and photographed in picturesque grayscale by his usual DP Jarin Blaschke. Neither is there fault to be found in its stars, as vulnerable, seething Pattinson plays a fine, flappable foil to Dafoe, whose rigorous, pitch-perfect delivery of truly challenging dialog as the tetchy shellback is remarkable for its fulminating intensity. However, a great movie doesn't necessarily proceed from a great performance, and though some of his themes concerning pretense, suppressed lust, homoeroticism, Oedipal variation, psychological duality, and so on are of some interest, his dramatic and emblematic illustrations thereof are more often ham-fisted than tastefully allusive, and largely disregard the American ethos of the late 19th century. A shot imitative of Sascha Schneider's painting Hypnosis looks great but plays stagily in sudden interpolation. An ithyphallic match cut for which a long shot of the titular lighthouse was to correspond to an erect penis was excised for commercial considerations, but isn't much more ridiculous than much else retained in the theatrical cut. Eggers imagines that a coherent story isn't necessary for fiction when his themes are so readily reified with ambience, symbolism, and histrionic extremities. That may be so for a masterful cinematic surrealist, but Eggers is no Buñuel or Polanski or Teshigahara, and this is neither scary nor clever.

Why, it's Hitler! By some unexplained science or sorcery, the choleric yet charismatic Fuehrer (Oliver Masucci) is restored to the location of his presumed death in the mid-teens, and following a period of cultural shock during which he's misrecognized as a gifted impressionist, finds employment as an (unintentionally) comedic telecast performer, pens a second bestselling memoir, and courts opprobrium for an canicide. Upon realizing that he's been promoting the genuine article, the pissant documentarian (offensively ugly Fabian Busch) who discovered him is horrified. As satire, David Wnendt's adaptation of Timur Vermes's eponymous novel is a justifyable hit; mauger some Americanized doltishness requisite in contemporary German pictures, it's played gamely by a deadpan cast and filled with laughable mishaps, anachronisms and references -- a scene parodying Bruno Ganz's much-memed tirade in Downfall is carefully parodied as a harangue of an executive (Christoph Maria Herbst) who castigates his underlings for his network's poor ratings. As propaganda, it's a horrible flop that only fortifies Hitler's recrudescent popularity -- especially by associating him with sensible anti-immigration and environmentalist policies. This only underscores the limits and faults of condemnation by association as a rhetorical tactic, even in instances involving the postwar creation myth's ultimate anathema. Scenes in which the despot uncharacteristically litters and shoots an aggressive little terrier to death do little for the movie's comedy or credibility. Vermes, Wnendt, and Constantin Film were all thrilled for the success of a book and movie that satirize the 20th century's most notorious celebrity; did any of them really consider all of the reasons why?

She's back at her childhood home sequent to a year of chic, grimy impoverishment misspent with her dirty, inane, unstable hippie boyfriend (David Carradine), but while her family's happy to have her back, a sweet, impressionable teenager (Sally Field) is pressured excessively by her hysterically overbearing parents (Jackie Cooper, Eleanor Parker) and pestered by a fatuous baby sister (Lane Bradbury) who's considering the prospect of vagabondage. Bruce Feldman's screenplay was clearly meditated as a relatively early exposure of dysfunction under the pleasant, plastic facade of suburbia; it only succeeds to communicate that parental solicitude is best expressed calmly, and that middle-class mundanity is a refreshingly luxurious and sanitary alternative to countercultural destitution. Characteristically competent oversight by Joseph Sargent wallpapers typically televised seams, and the dumb, bubbly frivolity of Field's gentle ingenue is sung by resemblantly gnomish cutie Linda Ronstadt in two exclusive songs.

A group of dedicated North Korean spies guised as a common family (Yu-mi Kim, Woo Jung, Byong-ho Son, So-yeong Park) photograph South Korean materiel and assassinate dissidents and defectors, but they can't harden their hearts against their squabbling neighbors (Byung-eun Park, Eun-jin Kang, Jae-moo Oh), or their actual families who they haven't seen in years -- and who'll surely be tortured and executed if their duties aren't fulfilled in precise compliance with commands from Pyongyang. Their resolve's eroded by sorrow, illness, the south's prosperous appeal, and unreasonable demands from their superiors until a grave and ambitious error begets a terrible tragedy. Ki-duk Kim's story broaches burning, essential points regarding both Koreas' statuses as oppositional puppets of suzerains China and the United States, the potential for their reunification, and the brutality by which the north's government destroys the lives of its human assets for minor advantages, but viewers must winnow his messages and many powerfully poignant scenes from others that are bathetically, frivolously stupid. Ju-hyoung Lee's direction of Kim's screenplay is unobjectionable, and his cast (excepting Kang, whose shrill overacting would be better suited to a farce) tackle their trying roles with convincing potency, though notice of either may be disrupted by the movie's ASL of 1.4 seconds. How did Kim (in coaction with one Heuk Kim), who edited his own directorial efforts with graceful deliberation, uncharacteristically overcut his production so egregiously that it's nearly unwatchable?

A washing machine purchased cheaply online by a construction manager (Hye-sun Shin) is used and broken; even after her spurned complaint, she probably wouldn't investigate to discredit the seller if she knew that he kills other urbanites to resell their personalty. That scamster's terrorization of his indignant vendee moves detectives (Sung-kyun Kim, Tae-oh Kang) to slowly track the serial slayer, but they can't keep her safe. Genre director Hee-gon Park's technically good but goofy thriller has plenty to recommend it and some sly sinuosity, but Shin's selfish, childless careerist isn't a terribly sympathetic victim in a nation afflicted with the world's lowest birthrate precisely because South Korean women would rather consume as corporate cogs than reproduce. It's fun if one can overlook its tired feminist clichés -- as a scathing, sexually frustrated boss (Chul-soo Im) -- and downbeat ending.

Overheated and overspoken though it is, its mysterious enticement and appealing leads make CBS's dramatization of Jane Stanton Hitchcock's first novel worth watching. A generous commission proffered by a wealthy widow (Ellen Burstyn) to massively mural the long-disused ballroom of her huge estate at first seems to be the choicest task for a conscientious painter (Meg Tilly) who's short of work, but a revelation regarding her employer's motivations, and the deceased daughter and debutante who's to be the cynosure of her artwork prompt her to reconsider her job. Everybody overreacts hysterically in Hitchcock's story and a worthless subplot therein, and its conclusion isn't terribly satisfying, but it's still a nice outlet for ever-robust Burstyn and Tilly, and one of the latter's last onscreen appearances as her career's first stage wound down.

=]=:< <"Bitchy old Celtic broad hires a pretty Sino-Celtic chick to paint shit and dress up like her dead daughter. How isn't this one of RoBu's stories?"

In his late father's home reside a filmmaker and his girlfriend, who entertain friends and a stranger with an exchange of three urban legends: a young actress -- who resembles a movie star that vanished after she was disfigured -- abandons her boyfriend when she comes under the roof and aegis of another superstar, whose intentions are by no means charitable; a street vendor and aspiring magician is discouraged by his religious, elderly father and menaced by strange spirits; parents of a vanished girl employ a medium to discover her remains, as well as a revelation that they already know. His cast is able and he sets his shots effectively, but Huu Tan Tran's anthology suffers irreparably for its godawful CG SFX and timeworn stories that have been better portrayed elsewhere. A subtler script that forgoes most of that gore could've saved this one.

Aboriginals (composer Wandjuk Marika, Roy Marika, Gary Williams, et al.) of south Australia object to and essay to peacefully deter detonations in their ancestral wasteland executed by a mining company that's searching for uranium. Their mystic certainty that mankind's extinction will eventuate from the destruction of weaver ants who scarcely populate the region falls on deaf ears, as evidenced by bribes offered its tribal elders -- a trip to Melbourne and the delivery of a massive green military airplane that fascinates their tribe. Who expected that one of Werner Herzog's most interesting movies would also be among his worst? His vast, often panoramic landscapes are as mesmerizing as usual, though his story amounts to little more than observation. Acting varies unsatisfyingly; cognate artists and activists Wandjuk and Roy Marika essentially play themselves with flat, monotonous credibility, but Bruce Spence leads as a geologist sympathetic to the tribe's concerns, and he hasn't the talent to justify his onscreen ugliness. If nothing else, Herzog's portrayal of aboriginals is wholly veracious: that of an indolent, meditative, deeply spiritual, simpleminded people whose unsophistication diverts outsiders from an attunement to nature and dedication to their traditions that most white urbanites couldn't imagine. Furthermore, it'll someday serve as a fine historical record of the absurd lengths to which ideologically backward white Anglos of corporations and judiciaries will go to appease primitive peoples for the satisfaction of public relations.

=]=:< <"Who gives a fuck about ants?! These people are as dumb as shit, and white people are too nice and ball-less to say anything about it. Fuck those ants! Let's have some more ponds for alligators. Oh, and this reminded me: most deserts and wastelands are for losers."

No other story authored by Agatha Christie enjoyed greater acclaim as a motion picture than Billy Wilder's filmic version of her stage play, but its esteem isn't wholly warranted. Fresh from a heart attack and subsequent hospitalization in his advancing years, an accomplished barrister (Charles Laughton) elects to defend an American (Tyrone Power) who's accused of viciously murdering the wealthy widow who bequeathed him her estate, but the conflicting and unreliable testimony of his German wife (Marlene Dietrich) is one of a few emergent factors that complicate his trial. There's no fault to be found in the finely contoured circuity of Christie's idiomatically intricate plot, and the attic wit of her dialogue is uttered with sly perfection by Laughton in a role to which no one else was better suited -- a surety substantiated by his impeccable courtroom manner, and repartee exchanged with his concerned and forbidding nurse (Elsa Lanchester) and his client's junior counsel (John Williams). Power looks and sounds terrific, but the calculated artifice of his thespianism is evermore glaring for its polish. That's more than one could say for bizarrely overrated Dietrich, who's as atrocious as usual, and an earsore when singing. Wilder's script (co-written with Larry Marcus and Harry Kurnitz) presents Christie's story well, except during an interposed, achingly asinine flashback that pictures how Power's defendant met his spouse, written specifically to showcase Dietrich's famed gams and grating voice. Laudation for its merits have apparently blinded most critics to the discomfiting flaws of Wilder's picture. One is reminded of the hokum that derails 12 Angry Men during its third act, when all present quietly ostracize Ed Begley during a bigoted tirade. In myriad forms and modes, Abrahamics love their sanctimony.

=]=:< <"Talk about mass delusion: who the hell told Dietrich that she could sing or act? RoBu's still seething about how much Boomers love Fonzie, but this bitch has to be the worst non-talent of her shitty-looking era. Imagine what it's like to hate Hitler so much that you convince yourself that this fucked-up, mannequin-looking twat doesn't sound like rutting cats are kidding? I swear to god, I hate Marlene Dietrich more than RoBu hates Sophia Takal. Her retard face scares me and she sucks at everything. Laughton was good, though."

What resolves or clarifies every societal problem and its personal microcosm while furnishing hilarity in the '70s? The road trip! That's the first resort of two friends, a buttoned-up shlub (Beau Bridges) who's bored with his menial office job and gentle, pestering fiancée (Janet Margolin) and one chronically irresponsible rip, credit junkie, and scamster (Ron Leibman) who flee the former's domestic cage and latter's progressively mountainous debt on a long drive that leads them through various misadventures right back to themselves -- their most uncomfortable destination. Low-budget comedic drama contrasts two lifestyles to emphasize their advantages and disadvantages as personified by Bridges's straight-laced dork and Leibman's hedonic profligate; screenwriter James Dixon didn't try in the least to make his characters likable, and the aptly cast leads can't either -- especially when the office veal played by Bridges denounces his girlfriend and resorts to violence over a minor dispute. Obviously, the uptight straight man just needs to relax, appreciate his neurotic but caring (and frankly gorgeous) future wife, and cavalierly disregard her petty demands; the spendthrift should relocate and obtain undemanding, part-time employment that'll keep him in cash while he plies legal schemes. One of three drastically different endings suggests that they've done so; another ends badly and horribly preludes at least one cut. Comparisons to Easy Rider/Five Easy Pieces/The King of Marvin Gardens/The Last Detail are inevitable, but Three Minutes has neither the urgency and profundity of Rafelson's movies, nor the pretensions of Hopper's. It also hasn't a star as emotively expansive as Nicholson, and as fit as they are, Bridges and Leibman can't create beyond the strictures of their shallow stereotypes.

© 2024 Robert Buchanan