by Robert Buchanan

Writers: Katsuhito Ishii, Yoji Enokido, Yoshiki Sakurai

Director: Takeshi Koike

Cinematographer: Ryu Takizawa

Editors: Naoki Kawanishi, Satoshi Terauchi

Seiyuu: Takuya Kimura, Yu Aoi, Tadanobu Asano, Takeshi Aono, Koji Ishii, Kosei Hirota, Unsho Ishizuka, Kenyu Horiuchi, Kenta Miyake, Kanji Tsuda, Yoshiyuki Morishita, Tatsuya Gashuin, Yoshinori Okada, Akane Sakai, Akemi, Cho, Shunichiro Miki, Ikki Todoroki, Daisuke Gouri, Yuichi Nagashima

Composer: James Shimoji

Producers: Yukiko Koike, Kentaro Yoshida, Daisuke Kimura, Ryoichiro Matsuo, Masao Morosawa, Akira Shinohara, Kiyotaka Ninomiya, Masahiro Fukushima

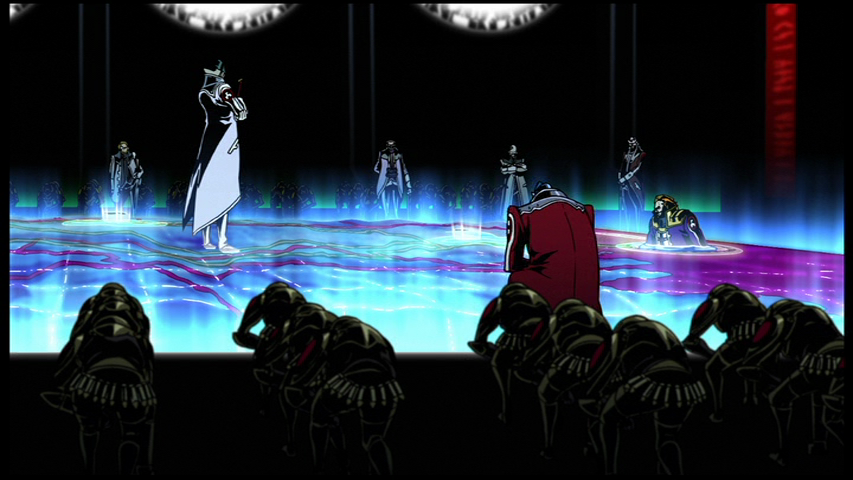

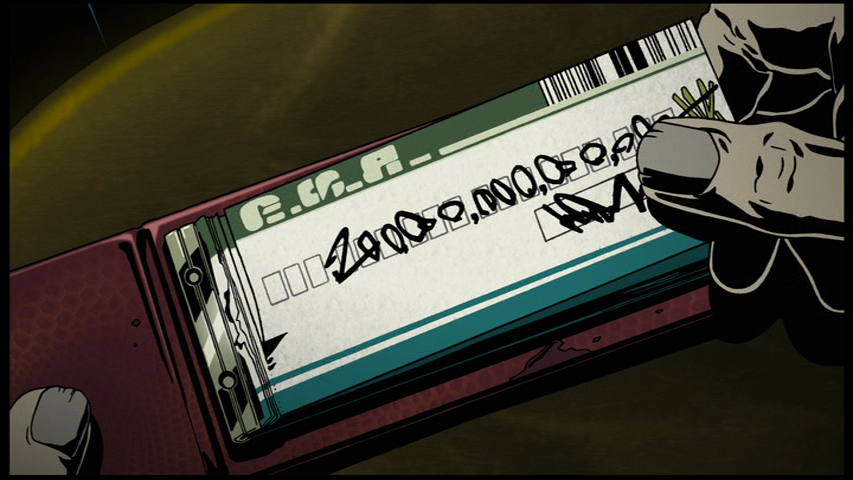

Lustral, galactically famed race Redline

Roboworld: barren, industrialized planet governed by militaristic cyborgs

Nearly every character's a caricature and most features thereof are outlandishly embellished and outrageously exaggerated as invented, sketched, and scripted by creator/co-screenwriter/production and character designer/sound director Ishii, whose own oddball, sometimes surrealistic comedies (Shark Skin Man and Peach Hip Girl, The Taste of Tea, Funky Forest: The First Contact, etc.) seldom have the singular focus and colorful intensity of his tribute to the subculture of American motorheads, Weekly Shonen Jump's vigorously masculine stories, and their themes of cooperation, friendship, and love. Appositely, he had sense sufficient to not decelerate his entertainment's breakneck pace with any burden of unneeded personal or interpersonal depth.

Footfalls daintily stepped to heavily stomped, squeaking leather, shifting mechanisms, sizzling food, roaring engines and explosions, and much more were superbly recorded, generated and sampled by Noriyuki Sakamoto, and mixed by Tsuneo Marui, Takeshi Imaizumi, and Tooru Kadokura under Ishii's demanding administration.

All of Redline's backgrounds, characters, and machines are represented by 100,000 painstakingly delineated, then digitally colored, enhanced, and composited drawings that were overseen (and often lined) by Koike, a longtime in-between, lead, and key animator, checker, and occasional designer at Madhouse, and for most of its famed co-founder Yoshiaki Kawajiri's most prominent theatrical and home video projects. His precise attention to supernumerary motional, terrestrial, vestural, anatomical and floral, fluidic and aquatic, fiery and explosive, and mechanical and electromechanical details insured an almost unparalleled quality perhaps overlooked by viewers stimulated by the bold, manic dynamism that he and Ishii indued to perspectives expected and otherwise, from sprawling landscapes and spacescapes to minutely clenching close-ups. Several prevenient collaborations with Ishii (as the prequel Trava Fist Planet) were preparatory for their silly, violent, incredibly sustained, and ever-amplifying pageantry.

Thousands of shots were cut by Kawanishi and Terauchi with such punctilious rapidity that intricacies therein would be wasted for most without the amenities of home video.

Four cinematic stars (Kimura, Aoi, Asano, Akemi) were as aptly cast and immediately recognizable as the veteran seiyuu with whom they were recorded. They're also the most restrained and nuanced of those heard on the soundtrack -- particularly in contrast to bass Koji Ishii, triumphantly vociferous Miki and Todoroki, seething Hirota, and shrieking, sobbing Miyake. For his foray into voice acting, Asano countered unexperience with his usual aplomb to coolly create the corrupt mechanic as expected by Ishii, in a few whose movies the leading man's starred.

Most memorable among James Shimoji's themes composed in distinct genres and styles therefrom for many scenes and all of Ishii's subjects are pounding, throbbing, chattering techno percussion at varying BPM, and guitars touched with buzzsaw distortion during the hell-for-leather races. It's recommended for pedalers and motorists alike.

Everything that discords with the wearisome doldrums of perfunctory pap, or existential ennui of Anno's overestimated Evangelion franchise and its tonal imitators that predominate contemporary anime are fresh breaths in what's become a profitably stagnant and involute industry. Seven years of fastidious labor begat this pulpy, science-fantasy masterpiece that flopped domestically, suggesting that contemporary Japanese have a limited appetite for shallow, spectacular anime. Nevertheless, diversions for cinephiles and otaku alike who are as voyeuristically tachymaniacal as Ishii's rivals are in action don't come better than this.

Writer/director: Woody Allen

Cinematographer: Carlo Di Palma

Editor: Susan E. Morse

Players: Mia Farrow, Dianne Wiest, Sam Waterston, Denholm Elliott, Elaine Stritch, Jack Warden, Rosemary Murphy, Ira Wheeler, Jane Cecil

Producer: Robert Greenhut

She's quietly adored by widowed Francologist Howard (Elliott), but fragile photographer Lane (Farrow) only has eyes for pessimistic copywriter Peter (Waterston), who's wrestling with his first novel and enamored with Lane's best friend, unhappily married pianist Stephanie (Wiest). Into Lane's cozy country home in Vermont -- and the skewed love quadrangle that's formed during their summer together -- barges her kind but callously brassy mother Diane (Stritch), a storied, former film star who's warmly remarried to contemplative physicist Lloyd (Warden). None of the amatorial secrets shared and secreted before and during Diane's arrival are as deep or dark as one harbored by Lane for years, and which sustains her enduring filial umbrage. Allen's sober, surpassing drama unfolds volubly in the manner of a stageplay, but isn't at all stagy for his deliberate and cinematic treatment, which follows his actors with observational tracking shots, zooms subtly at key moments, and delves with close-ups into intimacies spoken and silent. Not one misutterance mars the delivery of his optimally cast ensemble, whose creations of their seasoned, sensitive, wounded characters adopt the niceties and constrained passions of the living and breathing. In nearly every way, it's better than Allen's fine, flawed, critically lauded Interiors, but this briefer, wiser picture didn't enjoy its acclamation. Moreover, his uncharacteristic indecisiveness raised the film's budget to an absurd $10M because it was partially rescripted and entirely reshot after Sam Shepard, Charles Durning, and Maureen O'Sullivan were respectively replaced by Waterston, Elliott, and Stritch. Mostly eschewing the neurotic temperaments that typify so much of his fiction, Allen again excelled at the peak of his theatric powers by depicting people who are haunted by the past, needful in the present, reaching for or clutching each other, and suffering the terrible sting of unrequital.

Recommended for a double feature paired with its superior companion piece, Another Woman.

Writers: Yutaka Maekawa, Kiyoshi Kurosawa, Chihiro Ikeda

Director: Kiyoshi Kurosawa

Cinematographer: Akiko Ashizawa

Editor: Koichi Takahashi

Players: Hidetoshi Nishijima, Yuko Takeuchi, Teruyuki Kagawa, Haruna Kawaguchi, Masahiro Higashide, Ryoko Fujino, Takashi Sasano, Masahiro Toda, Toru Baba, Misaki Saisho

Composer: Yuri Habuka

Producers: Satoshi Akagi, Hiroshi Fukazawa, Satoko Ishida, Setsuko Sumida, Kota Kuroda

Trauma inflicted by an apprehended psychotic (Baba) deters him from further involvement in criminal affairs until a retired detective and professor of criminology (Nishijima) is reminded by his academic colleague (Toda) of a family's unsolved disappearance six years prior, shortly before his former subordinate (Higashide) invites him to probe this case to which he's reluctantly but ineluctably drawn. Freshly settled in a commuter town of west Tokyo, neither he nor his wife (Takeuchi) could imagine that his odd, tottering, mercurially tactless, apologetic, timorous, confrontational, loquacious, inimical, ingratiating, paranoid, chummy next-door neighbor (Kagawa) has anything to do with his investigation.

He's never been too shy to admit his stylistic debt to the greatest and most influential of all genre auteurs, but Kurosawa here waxes so Hitchcockian that this most conventional of his crime dramas verges on pastiche, so evident in his technique (memorably framed opening titles; allusive scuttlebutt; quietly significant dollied and zoomed shots; a rear-projected background; unnerving, even intimidating perspective shots) and script (first evidence disclosed at 57 minutes; a wrongly-arrested protagonist; unreliable police). Natheless, he doesn't refrain from reuse of his own hallmarks, as handheld shots stepped to and from subjects, creeping pans of wide shots, momentarily grisly close-ups, lingering disquietal that intensens to gripping suspense, and that foreboding, horribly applied transparent plastic. Kurosawa's professional retrospection is purely pragmatic.

When it isn't graded grimily green and gray to excess, Akiko Ashizawa's photography is satisfactory. A scene wherein an orphaned witness (Kawaguchi) recounts reemergent, material memories to Nishijima's criminologist darkens eerily during vocalization of her testimony.

Unforgettable in several of Kurosawa's past pictures as characters malign (Penance), sympathetic (Tokyo Sonata), or both (Serpent's Path), Kagawa has long proven himself one of the most idiosyncratically compelling living character actors of stage and screen. Any hack could unidimensionally portray his cowardly, casually contemptible and flagitious antagonist, but Kagawa created him with a comprehensive pathology that informs his peculiar, often discomfiting foibles and subtleties in a performance that insidiously slips under one's skin. Takeuchi's almost as impressively expressive of stifled, then fulminated frustration, inner conflict and torment. As protagonistic and deuteragonistic foils to their exceedingly dynamic co-stars, Nishijima and Higashide are as solid as the cast's remainder. Two differently traumatized daughters of destroyed families are underplayed with quiet conviction by model Haruna Kawaguchi and Aoi-alike Ryoko Fujino, whose captive schoolgirl's flat affect and suppressed dread lends to the story's ambiguity. Takashi Sasano endows the part of a canny old detective with quaint gravitas, and Masahiro Toda (a frequent minor player in Kurosawa's flicks since Cure and License to Live) is likably enthusiastic as a teacher thrilled to participate in matters detective.

Harmonic strings in minor keys sound most of Yuri Habuka's score to sparingly underscore pathos and menace, but never disrupt Kurosawa's carefully cultivated ambiences.

Fans who expected a return to the elliptic mysteries, offbeat chills, and black humor produced on small budgets of his best horrors and thrillers will be largely disappointed by Kurosawa's formalism, which here obliges an uncharacteristically satisfying climax. Yutaka Maekawa's novel was an ideally adapted vehicle for him to revisit the burden common to most of his fiction: potential peril proceeding from alienation and isolation in a gradually asocial Japan.

Writers/directors: Veronika Franz, Severin Fiala

Cinematographer: Martin Gschlacht

Editor: Michael Palm

Players: Elias Schwarz, Lukas Schwarz, Susanne Wuest

Composer: Olga Neuwirth

Producer: Ulrich Seidl

Is this facially bruised and bandaged, uncharacteristically severe and abusive, suspiciously ignorant and aberrant woman (Wuest) really the mother of venturous, inseparable identical twins (Schwarz brothers) repaired to their rural home after undergoing cosmetic surgery, or an impostor? Their efforts to authenticate render little satisfaction, and provoke progressively pestilent punishment. One equivocal enigma diverts from another equally, elegantly expressing the burden of Franz's and Fiala's slyly, strikingly storied and shot, eerie, eventually horrifying drama, which owes as much of its effect to natural, nuanced enactments as to its forbidding few clues, spared, shocking grue, and Olga Neuwirth's direful dissonances. With few intimations and fewer words do the directorial duad disclose what tragically drifts and lingers in hearts and minds: sport, kinship, doubt, ghosts....

Recommended for a double feature with A Tale of Two Sisters.

Writer/director: Ari Aster

Cinematographer: Pawel Pogorzelski

Editors: Lucian Johnston, Jennifer Lame

Players: Toni Collette, Alex Wolff, Gabriel Byrne, Milly Shapiro, Ann Dowd, Christy Summerhays, Morgan Lund, Mallory Bechtel, Jake Brown, Jarrod Phillips, Brock McKinney, William 'Bus' Riley

Composer: Colin Stetson

Producers: Scott E. Chester, Lars Knudsen, Kevin Frakes, Buddy Patrick, Jeffrey Penman, Brandon Tamburri, Beau Ferris, Tyler Campellone, Gabriel Byrne, Toni Collette, Jonathan Gardner, William Kay, Ryan Kreston

Strange, surplus mourners at her obdurate and contentious mother's funeral surprise an accomplished Utahn miniaturist (Collette) who's grappling with grief, and with many other portents presages the pernicious, eventual destruction of her discontented family (Byrne, Wolff, Shapiro). Of a superlative sort now rarer than four-leaf clovers, Ari Aster's fulsomely forewarning first feature is firstly a tragedy of terminal trauma, and dead second a horror that chillingly, intimately depictures their demoniac disintegration. The unheralded auteur meticulously plotted, planned, paced, and shot one of but a few truly unnerving American productions to enjoy mainstream distribution in the past thirty years, and his vision is substantiated by powerfully prime, predominantly practical effects, corresponding miniatures, and makeup crafted by makeup and prosthetic designer Steve Newburn with his Applied Arts FX Studio and key makeup artist Abigail Steele, Grace Yun's suitably detailed production design wherein subtly prefigurative, runic, and geometric symbolism are opulently incorporated, and a cast who do his shaded, formidable script justice, Before and during a slow discovery of arcana, Collette's bereaved wife, mother, and artist languishes, laments, recriminates, struggles, seethes, and suspects through stages of dolor with and against her husband and children, all of whom are represented with vehement credibility from a script that's almost so performatively operose as penetrative of its sorrowful burden. Her performance is a histrionic exemplar, and surely among the best of her career. Not one unneeded shot blemishes Aster's deliberations, and the skill by which his sweeping, panning, dollied perspectives, inventive subjectivities, match cuts, etc. were achieved belied his inexperience. It's distractingly macabre at first sight, but repeated viewings will reward argus-eyed viewers with allusions aplenty, and a few references to popular genre classics. As his posterior pictures to date indicate, Aster may never helm another masterwork, but this one's emotional lucidity, emblematic intricacy, and nightmarish ritualism boldly, horrifically dramatizes the corrosive and transformative power of tribulation, here conduced by demonolatry fueled by torment and sacrifice.

Recommended for a double or triple feature with Rosemary's Baby and/or The Babadook.

Writer/director: David Robert Mitchell

Cinematographer: Mike Gioulakis

Editor: Julio Perez IV

Players: Maika Monroe, Keir Gilchrist, Lili Sepe, Daniel Zovatto, Jake Weary, Olivia Luccardi, Bailey Spry, Ruby Harris, Leisa Pulido

Composer: Rich Vreeland

Producers: Rebecca Green, Laura D. Smith, Erik Rommesmo, David Robert Mitchell, David Kaplan, Robyn K. Bennett, P. Jennifer Dana, Mia Chang, Joshua Astrachan, Jeff Schlossman, Frederick W. Green, Corey Large, Bill Wallwork, Alan Pao

Most eyes can't see it, but to the vision of those who've been venereally cursed, a murderous ambulator slowly, silently, steadily stalks to dispatch them in the semblances of strangers and familiars. One such victim is a pretty, dégagé collegian (Monroe) who's maledicted by first congress with her boyfriend (Weary), and who like him can then only redirect the invisible monster by sex with another or others -- until he or they are killed. Every other shot of David Robert Mitchell's horror classic is fit for framing; his exquisitely expansive composition through wide-angle lenses exhibits the clarity of DP Mike Gioulakis's cinematography, and cozily, scruffily, nostalgically middle-class trappings of production design conducted by Richard Perry, all of which manifest the influence of Gregory Crewdson's implicitly lurid, strikingly cinematic photography. Such technical excellence only intensifies the early tranquility and eventual tensions of his broadly lensed, picturesque, static or creeping establishing shots, intimate close-ups, and mounted and hand-held pans that seize one's sight (especially one that's subtly yet sensationally staged in rotation exceeding 360 degrees, and terminates to a slow zoom), all of which are executed with a finesse that one might not expect in a sophomore feature. Nothing's needlessly belabored from the mouths of young, photogenic actors who were cast and costumed so markedly that their suburban Detroiters can be accurately assessed at a glance. Any few of Monroe's gestures or lines communicate her sensitive ingenue's ipseity; as easily gauged are her baby sister (Sepe), homely, crushing, unconfident childhood friend (Gilchrist), lusk buddy (Luccardi), and one handsome, horny, neighboring playboy (Zovatto). Comfortably slow to start but as exciting as frightful, Mitchell's perfectly paced picture's potentialities and ponderous themes unfold with a verisimilitude that matches his dialogue, and it's bereft of tiresome, contemporary slang or cell phones that might disrupt his retrospective aesthetics. Rich Vreeland's wholly synthesized, often Carpenterian music heightens the reflective and disquiet, halcyon and horrific atmospheres assiduously elicited by Mitchell, who also apprehends and applies effective silences. A few startling, unnoticed, unmentioned elements and details may only be espied in a second or third screening. In a context of suspense and existential dread, Mitchell represented how that vital act of pleasure, procreation, and love is defiled by betrayal, stigma, desperation, degradation.

Writers: Arthur Conan Doyle, Frank Gruber, Leonard Lee

Director: Roy William Neill

Cinematographer: Maury Gertsman

Editor: Saul A. Goodkind

Players: Basil Rathbone, Nigel Bruce, Patricia Morison, Frederick Worlock, Harry Cording, Carl Harbord, Holmes Herbert, Edmund Breon, Patricia Cameron, Mary Gordon, Ian Wolfe

Producers: Roy William Neill, Howard Benedict

Plain of make and tinkling prettily, three musical boxes manufactured at HM Prison Dartmoor are at an auction inexpensively obtained by as many bidders. One among them (Breon) is a longstanding friend of Dr. John Watson (Bruce), who introduces the bewigged collector to his companion and biographee Sherlock Holmes (Rathbone). Soon after this initial acquaintance, the acquirer is murdered and his seemingly unremarkable falderal is filched, and only the master detective and bumbling, burbling physician can ascertain how this crime relates to banknote plates stolen from the Bank of England. Rathbone and Bruce are in commonly fine form in their last of fourteen outings as Doyle's duo, which boasts some excitement and a puzzler that taxes the deductive faculties of the venerable London sleuth in opposition to three ruthless and wily criminals (Morison, Worlock, Cording). Neither the best nor worst of its series, it's a satisfying coda, and the penultimate picture of Irish journeyman Neill, who perished shortly thereafter in '46.

Recommended for a double feature with The Woman in Green.

Writer: Sakichi Sato

Director: Takashi Miike

Cinematographer: Kazushige Tanaka

Editor: Yasushi Shimamura

Players: Yuta Sone, Sho Aikawa, Kimika Yoshino, Shohei Hino, Renji Ishibashi, Keiko Tomita, Harumi Sone, Sakichi Sato, Kanpei Hazama, Tamio Kawachi, Susumu Kimura, Hiroyuki Nagato, Hitoshi Ozawa, Kazuyoshi Ozawa, Tokitoshi Shiota, Tetsuro Tamba, Yoshiyuki Yamaguchi, Kenichi Endo, Masaya Kato, Cavid Chao

Composer: Koji Endo

Producers: Harumi Sone, Kanako Koido

A municipal dump in Nagoya was to be the fatal destination of a yakuza's psychotically paranoid underboss (Aikawa), who's transported by his loyal, conflicted underling (Sone) at the behest of their deviant honcho (Ishibashi). He's apparently, accidentally killed en route, and when his body vanishes in a shabby suburb of the central city, the frantic enforcer's taxing, tortuous search for it leads him to the transvestic staff of a restaurant and its effeminately huffy proprietor, chef, and waiter (screenwriter Sato); verbigerating locals (Hazama, Kawachi); a low-rent crime family, of whom a lonesome, vitiliginous layabout (Hino) is a member; aging, abnormal siblings (Tomita, Sone) who host at their modest inn; phlegmatical car crushers (Tamba, Yamaguchi) of that destined dump; various other oddballs; a flaky, flirtatious beauty (Yoshino) who unaccountably knows and contains surprising secrets. Sato's and Miike's slow, cozy, spooky, quasi-horrific, genuinely bizarre and hilarious crime comedy vacillates unpredictably from batty action to dry deliberation from the perspective of Sone's bewildered gangster as a choice foil to most of his wry co-stars. That signature interchange of jocular and deadpan wackiness that made Aikawa a star of V-Cinema was seldom if ever so effectually exploited among his many collaborations with this prolific artificer as it was here. In a colorful supporting cast full of familiar faces, typecast Ishibashi is perfectly stern and perverted as the gang's kinky, imperious leader, Tomita unnerves in her temperamental part as the sororial hotelier, and stolid Tamba's reiterative cameo is as simple as memorious. His distinctively dynamic and tightly controlled approach enabled Miike to endue focus to Sato's surreal, serpentine story, which is weird even by Japanese standards, and demonstrative of comedy's only rule.

Writers: Clemence Dane, Helen Simpson, Alma Reville, Alfred Hitchcock, Walter C. Mycroft

Director: Alfred Hitchcock

Cinematographer: Jack E. Cox

Editors: Rene Marrison, Emile de Ruelle

Players: Herbert Marshall, Edward Chapman, Norah Baring, Esme Percy, Phyllis Konstam, Marie Wright, Miles Mander, Gus McNaughton, Donald Calthrop, S. J. Warmington, R.E. Jeffrey, Alan Stainer, Kenneth Kove, Guy Pelham Boulton, Violet Farebrother, Clare Greet, Drusilla Wills, Robert Easton, William Fazan, George Smythson, Ross Jefferson, Picton Roxborough, Joynson Powell, Una O'Connor, Hannah Jones

Composer: John Reynders

Producer: John Maxwell

Surely the young actress (Baring) who was found dazed and seated beside both the corse of another with whom she'd been feuding and the poker used to larrup that actorine to her death is guilty! That's the indictment put to the jury of her trial, which after lengthy, sympathetic, rational deliberation, and the reluctant incertitude of the famed actor (Marshall) among its dozen, delivers a verdict of guilty. However, that redoubtable thespian's questioning conscience, instincts, and realization after the accused has been sentenced oblige him to further inquire into the crime's scene and circumstances, accompanied by the condemned and terminated ladies' stage manager (McNaughton) and his clumsy wife (Konstam). Hitchcock's third talkie divertingly delivered Clemence Dane's and Helen Simpson's novel Enter Sir John to the screen, and blazons ambitious traveling shots, silhouetted activity, picturesque and successively dissolved establishing shots, two cunning match cuts, and a playful pan that already distinguished the tubby cineast from his contemporaries, and constituted some of the many devices that he'd refine over the next four decades. A quality cast headed by genial Marshall hit their marks splendidly to realize abundant drama balanced with humor both broad and genteel, a refreshingly racist reveal that'll exasperate egalitarians, and no small suspense during the third act. A Germanophone version titled Mary was populated by different players, shot concurrently on the same sets, and released the following year. Simpson's novel Under Capricorn was also cinematized by Hitchcock 19 years later. Attentive fans will glimpse Hitch as a passing pedestrian. Newly yielded to the public domain last month, Murder! may now be freely viewed by anyone keen to observe this master's inchoate manner.

Recommended for a double feature with The 39 Steps.

Writer: Alan Sharp

Director: Arthur Penn

Cinematographer: Bruce Surtees

Editors: Dede Allen, Stephen A. Rotter

Players: Gene Hackman, Jennifer Warren, Susan Clark, Edward Binns, Harris Yulin, Janet Ward, Melanie Griffith, James Woods, John Crawford, Kenneth Mars, Anthony Costello, Ben Archibek

Composer: Michael Small

Producer: Robert M. Sherman

Without their cohabitation, a former actress (Ward) can't access the trust fund bequeathed to her bed-hopping, runaway daughter (Griffith), so a tough, keen private dick (Hackman) in her employ seeks the cute teen first in New Mexico, then the Florida Keys, and finds his target, but chances upon a plot to smuggle valuable artifacts from Yucatán that's sufficiently lucrative to instigate a few murders. Sharp's and Penn's introspective noir mystery is more focused on its people than its plot, and consequently flopped despite enduring, sometimes overestimating critical praise. The late, great Mean Gene hasn't a false note in him, and his expressions of acrimony, affection, frustration, reflection, regret and more consist honestly for his recognition that none of them are discrete. He interplays perfectly with a rock-solid supporting cast; of particular note are Clark as his caring yet unfaithful wife, twitchy Woods cast in the part of a sleazy, expert mechanic, Warren playing the weathered girlfriend of his employer's ex-husband, and especially recently deceased Yulin, who goes tensely toe to toe with Hackman in a heated, almost violent confrontation when the PI tracks down his spouse's lame, well-to-do lover. The 1970s were an era when robust American masculinity assumed a confused, doubtful, disillusioned aspect that Hackman embodied with sensitivity, durability, believability -- here striving for professional purpose in the absence of personal fulfilment. It isn't Penn's best picture (in part because The Missouri Breaks was released a year later), but Moves showcases its lead at his most engagingly shaded. We may not see his like again.

Recommended for inclusion in a marathon with The French Connection, The Conversation, French Connection II, The Package, et cetera, for observation of Hackman's versatility as heterogeneous investigators.

Writers: Akira Kurosawa, Hideo Oguni, Djordje Milicevic, Paul Zindel, Edward Bunker

Director: Andrei Konchalovsky

Cinematographer: Alan Hume

Editors: Keith Corder, Henry Richardson

Players: Jon Voight, Eric Roberts, Rebecca De Mornay, John P. Ryan, Kyle T. Heffner, T.K. Carter, Kenneth McMillan, Stacey Pickren, Walter Wyatt, Edward Bunker, Reid Cruickshanks

Composer: Trevor Jones

Producers: Sue Baden-Powell, Menahem Golan, Yoram Globus, Henry T. Weinstein, Robert A. Goldston, Robert Whitmore

Their grimy, then gelid escape from a maximum-security penitentiary through its sewers, then the wintry landscape beyond isn't a tenth as harrowing as the adventure to which a famed bank robber and serial escapist (Voight) and his dopey, ebullient fellow felon (Roberts) are destined when they board a freight train that's unmanned after its engineer drops dead, and unrestrained in velocity after its brake shoes burn away and it collides with another train's caboose. Their career by tracks might be meliorated by ministration of an onboard assistant hostler (De Mornay), and the railway's local supervisor (McMillan) and dispatchers (Heffner, Carter), but the sadistic, magisterial, grandstanding warden (Ryan) of their recent prison pursues his sometime inmates by helicopter without intention to take them alive. It isn't the masterwork that it might've been had Akira Kurosawa delivered his and Hideo Oguni's story to the screen instead of the ill-fated Dodes'ka-den, but Russian emigre Andrei Konchalovsky's clamant, campy, powerful handling of his tale is nonetheless as exciting and affecting as actioners come, charged with the masculine energies of its seethingly aggressive, eventually reflective leading men and top-flight practical effects that leave little to one's imagination. With that boundless vim aforeseen in The Pope of Greenwich Village, Roberts plays his daft yet devoted partner to irately expressive Voight well over the top, and both are great at both their hammily wild and pensively sedate extremes. Those calms between his histrionic storms are where Konchalovsky unveils his characters' inner vulnerabilities and strengths, and even when his movie veers melodramatically, its appealing balance of drama and violence is as riveting and honest as any in its genre. Its otherwise excellent production values are marred slightly by a few corners typically cut in flicks by Golan-Globus: exterior shots of the pen are plainly matte paintings, and bad dubbing (especially during the first twenty minutes) undercuts some of the acting. However, Konchalovsky finely frames most of his shots to maximize their explicit grit and realism; that latter lineament's furthered by the presence of genuine ex-convicts Danny Trejo (in his first role, battered by welterweight Roberts in their prison's boxing ring) and co-screenwriter Eddie Bunker as an overloyal comrade to Voight's esteemed lifer, as well as towering wrestler "Tiny" Lister in the part of a friendly prison guard. Never mind what could've been; through Konchalovsky's eyes, The Emperor's vision has more heart and white-knuckle might than that virtuoso might've clothed -- though its transcendently sacrificial conclusion is as ethnomatically Japanese as one could expect.

Writers: Aleksandar Radivojević, Srdan Spasojević

Director: Srdan Spasojević

Cinematographer: Nemanja Jovanović

Editor: Darko Simić

Players: Srdan Todorović, Sergej Trifunović, Jelena Gavrilović, Slobodan Bestić, Katarina Zutić, Miodrag Krcmarik, Lena Bogdanović, Andela Nenadović, Ana Sakić, Nenad Heraković, Lidija Pletl, Luka Mijatović

Composer: Sky Wikluh

Producers: Srdan Spasojević, Nikola Pantelić, Dragoljub Vojnov

Why do so many who've watched Srdan Spasojević's goofy, gory, goatish, allegoric, Eurotrashy sex thriller take it so seriously? It prompted performative outrage from embarrassingly effeminate film critics, censorship in numerous markets, and widespread denunciation, but few noticed how blackly comedic it is in its excoriation of Serbian society. Renowned for his indefatigable libido, copulatory stamina, and elephantine endowment, a quondam pornstar (Todorović) who's settled into casual alcoholism and familial placidity with his adoring wife (Gavrilović) and son is solicited by one of his sluttier co-stars (Zutić) to perform once more for a moneyed, manically magnetic smutmonger (Trifunović), whose gushing cajolery for the hugely hung stud is substantiated by the unspeakable lucre of his profferred fee. His participation constrains performance of thitherto unfamiliar sadomasochism that soon skews into criminality, none of which is optional. With notably professional proficiency, Spasojević frames and supervises his histrions in accordance with his and Radivojević's incisively allusive script, which evidences the sincerity of their message regarding Serbia's cycles of lifelong brutality and exploitation, but hardly disaffirms the suspicion that their admittedly substantive burden was also an excuse to produce one of the most vicious, depraved, ithyphallic motion pictures to which international distribution was conferred. This cast is acutely attuned to their parts, and they perform plausibly even during their most inane iniquities -- especially Trifunović, who's accorded the lion's share of lewdly amusing dialog to play his philosophastering pornographer right to but not quite over the top. For viewers who like fiendish, ruinous violence and lascivity, this should fit the bill; those with tender hearts and stomachs will find more palatable fare elsewhere. Radivojević and Spasojević belabor their transgressive reprehension of Serbia as a land of depredation, but might've noticed another evident theme: that sex sundered from procreation and love is a direct route to turpitude.

Writers: Jason Cohen, Steven Leckart

Director: Jason Cohen

Cinematographer: Svetlana Cvetko

Editor: Jake Pushinsky

Subjects: Rod Canion, Jim Harris, Bill Murto, Ben Rosen, Mitch Kapor, Gary Stimac, Karen Walker, Bill Aulet, Chris Garcia, Bob Jackson, John Markoff, Bill Fargo, Charles Lee, Howard Anderson, Kim Francois, Ross Cooley, Hugh Barnes, Steve Ullrich, Steve Flannigan, Mike Swavely, Roger McNamee, Christopher Cantwell, Ken Price

Composer: Ian Hultquist

Producers: Ross M. Dinerstein, Glen Zipper, Lydia Dunham, Steven Leckart, Jason Cohen, Samantha Housman

Profuse personal and professional photographs, excerpts from newspapers, magazines, archival footage of televised commercials and news, financial, and technological programs, and interviews with commentators (Garcia, Markoff, Anderson), associated industrial veterans (Kapor, McNamee), whilom staff of IBM (Aulet, Jackson), Compaq's founders (Canion, Harris, Murto), chairman and initial investor (Rosen), and employees (Stimac, Walker, Lee, Francois, Ullrich, Flannigan, Cooley, Barnes, Swavely, Fargo, Price, etc.) constitute the meat of this gimmicky, personal, informative documentary, which recounts the storied, alacritous ascent of Compaq during the 1980s from a minuscule tech startup in '82 to the preeminent manufacturer of personal computers twelve years later. When first fording their glutted yet fertile emergent consumer market, the Houstonian trio distinguished themselves to immediate lucre by realizing their first product: a rugged luggable compatible with IBM's software and superior to a few underwhelming, bunglesome predecessors. The Compaq Portable evinced its firm's scrupulous attention to quality control and consumers' expectations -- paramount considerations owing to the same munificence of fathering executives who established an unbureaucratic, meritocratic corporate culture that was receptive to the input of its work force. At its best, Cohen's account vividly details with lime infographics the Texan manufacturer's challenges, exploits, victories, and celebrations: grueling conciliation with software and hardware designed for IBM's microcomputers without consultation of their published references to avoid infringement of copyright; managerial contention with nearly exponential internal expansion; interoperability of products that surpassed IBM's own; humorous telecast commercials starring John Cleese; glitzy introductions of products that featured performances by notable entertainers (The Pointer Sisters, David Copperfield, Irene Cara); retaliatorily litigious threats by behemoth Big Blue in pertinence to semi-legitimate patent claims; the intercorporate development of the intercompatible EISA bus standard with eight fellow manufacturers of IBM-compatible PCs (AST, Hewlett-Packard, NEC, Olivetti, Seiko Epson, Tandy, WYSE, Zenith) in cooperative, diametric response to the Micro Channel architecture of IBM's disastrously uncompatible PS/2; aggressive competition from upstart Dell; Eckhard Pfeiffer's push for higher volume at lower cost as Compaq's executive of European and Asian operations, president of its North American division, COO, then CEO after Rosen convinced the company's board to terminate Canion for failing to resolve a slump in sales and massive subsequent losses. At its worst, it lapses into an advertisement for AMC's overtly silly docufictional series Halt & Catch Fire for incorporated clips thereof and needless, obnoxious exposition by its co-creator, Christopher Cantwell. The ambition by which three middle-class family men dissatisfied with their employment at Texas Instruments instituted an enterprise that rose to rival their industry's preponderant leviathan in less than a decade can't be readily overstated -- mauger hyperbole of certain interviewees.

Writer/director: Bryan Bertino

Cinematographer: Peter Sova

Editor: Kevin Greutert

Players: Liv Tyler, Scott Speedman, Gemma Ward, Kip Weeks, Laura Margolis, Glenn Howerton

Composers: tomandandy

Producers: Nathan Kahane, Doug Davison, Roy Lee, Thomas J. Busch, Joseph Drake, Marc D. Evans, Kelli Konop, Trevor Macy, Sonny Mallhi

At first knock on the door of a rural summer home where a troubled couple (Tyler, Speedman) are vacationing, a trio of masked, shrewd lunatics (Ward, Weeks, Margolis) who've come calling late at night know that they've found the targets they'll terrorize with tactics sly, sportive, sadistic. Bryan Bertino's deceptively simple directorial debut is cunningly plotted, shot dexterously and unindulgently by hand and Steadicam, tightly cut, and played well -- especially by Tyler, who hits her grueling marks with believably jolted hysterics. Long-tarnished by tacky, unscary, perennial sequels and remakes (particularly of superior Japanese and Korean productions), the reputation of American horror cinema was much meliorated during the late aughts through teens by a surge of smart, economical productions, few of which enjoyed this one's nationwide, then international distribution and franchise. To considerable effect did Bertino refresh creepy niceties, jump scares, sinuate suspense, and the inexpungible musk of the '70s.

Recommended for a double feature with The Sitter, When A Stranger Calls, Them, You're Next, or Creep.

Writer/director: Thomas Woodrow

Cinematographer: Shabier Kirchner

Editor: Matt Posey

Players: Louisa Krause, Aaron Stanford, Doug Jones

Composer: Mark Korven

Producers: Naomi Wells, Michelle Cameron, Tamara Fisch, Paul Mezey, Noah Millman

After years of vagation through a partially irradiated wilderness, two quasi-amnestic survivors (Krause, Stanford) chance upon a desolate hotel of twain towers that contains superabundant shelter and sustenance, inexplicably advanced technology, language written and printed in alien characters, reel-to-reel recordings of unfamiliar music and abstruse accounts, and an inert man (Jones) long lain in a drained, mossy swimming pool. The mystery upon which Woodrow's ingenious story is predicated wasn't meant to be fully solved, but contributes to demonstration of several themes, among them how falsehoods and secrets may destabilize relationships, civilization isn't readily regenerative, and its absence stunts maturation. His unostentatious but memorable framing, and fullhearted portrayals from his thespian trio are as commendable as Rayna Savrosa's production design, which actualizes postwar, tacitly Soviet trappings that mesh well with elements of science-fantasy. Occasionally recalling his music composed for The Witch a year before, Mark Korven's alternately charming and dire score for synthesizer, ensemble, and choir amplifies the eerie ambiance emanative from Woodrow's aboundingly allusive feature, which suggests that if Shangri-La exists, it's never an extrinsic locale.

Writers: Evan Hunter, Philippe Labro, Jacques Lanzmann, Vincenzo Labella

Director: Philippe Labro

Cinematographer: Jean Penzer

Editors: Claude Barrois, Nicole Saunier

Players: Jean-Louis Trintignant, Dominique Sanda, Sacha Distel, Carla Gravina, Jean-Pierre Marielle, Laura Antonelli, Paul Crauchet, Stéphane Audran, Erich Segal, André Falcon, Esmeralda Ruspoli, Alexis Sellan, Michel Bardinet

Composer: Ennio Morricone

Producer: Jacques-Éric Strauss

In less than 48 hours in sunny, coastal Nice, two scarcely acquainted businessmen (Bardinet, Sellan), a Swiss astrologer and drug dealer (Segal), and a dental assistant (Gravina) are felled by .22-caliber rounds discharged from a marksman's long rifle, and the motive for these killings is initially as unknown to the peremptory, ablutomaniacal, crack-shot detective (Trintignant) heading their investigation as the nexus binding these victims. A sinful secret at the heart of Ed McBain's novel Ten Plus One links the assassinated to the assassin and one another, and it's buried in the third act of this French transposition that's sometimes crudely but always effectively helmed by Labro, whose deliberately elicited suspense fixates before snapping to periodic action. With a touch of chilly charm, Trintignant's as impeccably aloof as usual, like many among his able co-stars. Morricone's percussive, brazen and whistled, variably jaunty and eerily ominous score tonally grounds and augments Labro's pleasantly presented, sun-baked exteriors and tense miasms. It's enjoyable for anyone partial to murder mysteries and police procedurals, and absolutely required viewing for devotees of its offish leading man.

Recommended for a double feature with Cat o' Nine Tails.

Writer: Simon Barrett

Director/editor: Adam Wingard

Cinematographer: Andrew Droz Palermo

Players: Sharni Vinson, Nicholas Tucci, Wendy Glenn, AJ Bowen, Joe Swanberg, Margaret Laney, Amy Seimetz, Ti West, Rob Moran, Barbara Crampton, L.C. Holt, Simon Barrett, Lane Hughes, Larry Fessenden, Kate Lyn Sheil

Composers: Mads Heldtberg, Jasper Lee, Kyle McKinnon, Adam Wingard

Producers: Simon Barrett, Jessica Wu Calder, Keith Calder, Kim Sherman, Chris Harding, Brock Williams

To their sylvan manse, a wealthy couple (Moran, Crampton) invite their offspring (Swanberg, Bowen, Tucci, Seimetz) and their partners (Laney, Vinson, Glenn, West) to a conciliatory regale that degenerates into disputation just before they're assaulted by bemasked intruders (Holt, screenwriter Barrett, Hughes) armed with crossbows and axes, who didn't expect that one of these guests snares, fights, and kills at least as deftly as they do.

Clever clues, misdirecting moments, a red herring, shameless jump scares, and genuinely funny, mostly argumentative, often pitch-black humor abound in Barrett's quickly-paced script, which is actualized in commodious establishing shots, tightly framed close-ups, smooth zooms, significant slo-mo, frantic action, and plenty else thoroughly cut and charged with a persisting elan that maximizes their effect -- a significant idiomatic advancement for Wingard, whose previous picture consists almost exclusively of direct, handheld shots. Scenes depicting flight and fight alike are as consummately choreographed and performed as shot, much to the credit of stunt coordinator Clayton J. Barber.

Familiarity with this cast drawn largely from Larry Fessenden's and Joe Swanberg's circles may foretoken how long their respective characters last. Playing a student and slam piece of Fessenden's neighboring professor, shapely butterface Sheil thankfully hasn't any lines to woodenly misvocalize, and probably reenacts here how she and her closest collaborator* secured many of their roles during their professional ascendance. Fessenden's continual experience as a corpse consigns him to a gruesome early demise. His once-ingenious protege West and prolific *Seimetz (cast against type as the bubbliest of the ladies assembled) are similarly, predictably marked. Portrayals are fine and wry all around: Swanberg's a particularly amusing, agitatively caustic big brother to Bowen's insecure academic; scream queen Crampton still clamors chillingly, but she's excelled in that capacity by Laney, who personates her snide, pampered, then brutalized ice queen with an intensely hysterical stridence that isn't overplayed; slim, slightly rugged Vinson's approach to her circumstantial survivalist is charming, then understated in delivery, but conversely emphatic in action, and consequently almost creditable.

This fourth of their first eight collaborations in five years is Wingard's and Barrett's best: a wholly well-crafted thriller in which their usual gruesomeness and silliness is properly balanced, unlike A Horrible Way to Die's grim solemnity punctuated by abashing bathos, or the occasionally overt inanity of their fun, flawed fan favorite, The Guest. It's also qualitatively and tonally representative of the best horrors and thrillers that were economically produced by independent American filmmakers during the late aughts through mid-teens: a jarring, comical, bloodsoaked massacre wherein only a single gunshot's discharged! For all save the most amnestic or unmusical viewers, it'll leave Dwight Twilley's Looking for the Magic on mnemonic repeat for at least so long as its runtime.

Recommended for a double feature with The Strangers.

Writer/director: Michael Goldenberg

Cinematographer: Adam Kimmel

Editor: Jane Kurson

Players: Mary Stuart Masterson, Christian Slater, Pamela Adlon, Ally Walker, Debra Monk, Brian Tarantina, Josh Brolin, Kenneth Cranham, Mary Alice, Anne Pitoniak, Michael Haley, Cass Morgan, Gina Torres, Nick Tate, Víctor Sierra, Michael Mantell, Zachary Chaltiel, Claire Jacobs, Yvonne Zima, Desiree Casado, Leah Pepper, S.A. Griffin

Composer: Michael Convertino

Producers: Allan Mindel, Denise Shaw, Michael Haley, Kim Moarefi, Lynn Harris, Joseph Hartwick

Her juvenile orphanhood is the foremost inhibitor and secret shame of an ergophilic banking executive (Masterson), but doesn't concern anyone else, as her supportive best friend (Adlon), the widowed florist (Slater) who woos her with extravagant bouquets, or his warmly Rockwellesque family (Walker, Monk, Haley, Pitoniak, Morgan, Mantell, Torres, Tate, Chaltiel, et alia). Much can be commended of occasional screenwriter Goldenberg's sole, shiny, syrupy, slightly stodgy directorial effort, as DP Kimmel's beautiful cinematographic color and clarity, or credibly emotive leads in the last years of their stardom, who are met well by their co-stars. Alas, the prolongation of his story and its stinted conflict hinges on his protagonist's neurotic reserve, and though it's worthwhile viewing for anthophiles or nostalgic GenX fans of Masterson and Slater, they can only impart so much personality to such decidedly limited characterization. As Christmas romances come, it suffices.

Writers: Arnold Somkin, Doug Chapin

Director: Noel Nosseck

Cinematographer: Stephen M. Katz

Editor: Robert Gordon

Players: Richard Hatch, Doug Chapin, Susanne Benton, Ann Noland

Composer: Rick Cunha

Producers: Paul Cowan, Noel Nosseck

"What do you mean, we can't afford it? We deserve it." Seldom have more Boomerish sentiments been uttered than that of a responsible young man (Hatch) who, with his shell-shocked, newly discharged buddy (Chapin) and their cute fiancées (Benton, Noland) rent an RV to cross the southwest on vacation, on their way back home to California. Alas, the unhinged Vietnam veteran's increasingly unstable manner and perseverance to negate their engagements in anticipation of endless adventure results in infidelity, an attempted rape, escalating violence, and a climactic homicide. With marginal adeptness did future TV director Nosseck wrangle his first feature, an early, seedy vetsploitational drama that's paced and acted well enough to overcome Somkin's crude characterizations, though not his ruefully pointless end. A better story that actually amounts to something would've illuminated these friends who've divergent goals and inverse outlooks through equipollent frolic and hazard, rather than waste its photogenic, naturalistic quartet on salacious and sordid situations. Fans of Battlestar Galactica may find interest in handsome Hatch a few years before that show aired.

Writers: E. L. Konigsburg, Michael De Guzman

Director: Joseph Sargent

Cinematographer: William Wages

Editor: Paul LaMastra

Players: Stephanie Zimbalist, Shawn Phelan, Pamela Reed, George Grizzard, Jenny Jacobs, Libby Whittemore, Dorothy McGuire, Patricia Neal, John Evans, Barbara Britt, John Bennes, Judith Sullivan, Mary Nell Santacroce, Dan Albright, Warde Q. Butler, Joseph C. Floyd, Marc Gowan, Alice Heffernan-Sneed, Randi Layne, Mark Lee Levitt, Jeff Young Lewis, Lonnie R. Smith Jr., Tonea Stewart, Bruce Taylor

Composer: Charles Bernstein

Producers: Dorothea G. Petrie, Paul A. Levin, John Beaird, Les Alexander, Joseph Broido, Dan Enright, Don Enright, Barbara Hiser

Is a charitable, mundivagant nurse (Zimbalist) actually a former debutante long-imagined dead in an aviatic crash years before, daughter to a paternally negligent investor (Grizzard), daughter-in-law to his overbearingly bitchy second wife (Reed), aunt to their nerdy son (Phelan) and hobbled, pampered, putatively retarded daughter (Jacobs)....or just an opportunistic impostrix? As her reappearance coincides with the impendence of her matrilineal inheritance, an investigation initiated at the aforementioned termagant's behest is eventually overshadowed and presumably abandoned when the possible changeling focuses on how her suspecter's little girl has been stunted by mommy's controlling overindulgence. We who haven't read Father's Arcane Daughter by one E. L. Konigsburg can only hope that his novel isn't as artlessly expositional or schmaltzily overdramatic as De Guzman's teleplay therefrom, which compels from its cast consistently irritating overacting of stilted dialogue, and in which nobody can be bothered to recall, much less mention blood types or dental records. A few attractively framed shots recall Sargent's best pictures from the '70s, but his effort in helming this well-costumed but middling melodrama is otherwise perfunctory; god knows he didn't once enjoin his players to refrain from gnawing their scenery. Simply conceived yet sloppily and flabbily plotted, Konigsburg's umpteenth variation of the noble pretender misrepresents ruinous altruism as summum bonum in a post-Christian, proto-feminist context, positing women's independence as a counterpoint to neurotic familial dysfunction. Insinuation of that kosher dialectic is the sole subtlety of such an oppressively hackneyed domestic psychodrama, which reminds one of just how wearisome these had become on page and screen by the '90s.

Writer/director: Mickey Keating

Cinematographer: Mac Fisken

Editor: Valerie Krulfeifer

Players: Lauren Ashley Carter, Brian Morvant, Sean Young

Composer: Giona Ostinelli

Producers: Mickey Keating, Jenn Wexler, Sean Fowler, Chris Skotchdopole, Tim Wu, Larry Fessenden, Lauren Ashley Carter

The homeowner (Young) of an old, opulent, reputedly haunted house in NYC intrusts it awhile to the care of a young, traumatized schizophrenic (Carter). What could go wrong?

His usual sharp style and skimpy substance underserve Keating's ludicrously overcut homage to Polanski's Apartment Trilogy, for which talent and resources were misspent by a director who makes a succulent portrait of his every shot with concepts wholly on loan.

Instead, watch Repulsion, Images, or The Tenant.

Writers: Koji Suzuki, Yuuka Tanaka

Director: Yohei Fukuda

Cinematographers: Kazuhiro Mimura, Yohei Fukuda

Editor: Yasutake Torii

Players: Marika Ito, Taichi Yamada, Keiji Nakagawa, Kosuke Endo, Seiko Ozone, Yosuke Nishi, Akari Yamada, Yue, Aika Kobayashi

Composer: 34423

Producers: Koji Saito, Yuji Yamano, Makoto Yamaguchi, Takafumi Ohashi, Akira Ishii

Her late best friend (Yamada) is one of two spirits haunting a teenager (Ito) who can't fathom why, or how her family's disintegrating as she agonizes to guard her baby brother (Nakagawa) from the consequences of secrets kept by her friendly father (Yamada) and splenetic mother (Ozone). Ring and Dark Water were successfully adapted and franchised from two of Koji Suzuki's best novels, but this drab, dreary, dour J-horror drawn from one of his short stories is hardly so engrossing, and Yuuka Tanaka's screenplay diminishes what might've been a mildly occupying, apparitional mystery into a plodding, predictable, convoluted melodrama that feels far longer than its run time of 94 minutes. Yohei Fukuda's direction is as operative as the performances of his cast, particularly that of subtle Ito (formerly a singer and dancer of idol group Nogizaka46) in her first leading part, but neither can negative this story's glaring clichés or leaden pace. Ordinarily dingy chromatic grading and tacky, jittery effects applied to flashbacks conform this production to most others of a subgenre that was by the mid-teens a decade past its expiration date.

Instead, watch A Tale of Two Sisters or Goodnight Mommy.

Writers: Tracy Sinclair, Rosemary Anne Sisson, Jim Henshaw

Director: Donna Deitch

Cinematographer: Nyika Jancsó

Editor: James Lahti

Players: Andrea Roth, Rick Springfield, Stephanie Beacham, Geordie Johnson, Ian Richardson, Viktoria Kerekes, Kathleen Gati, Zoltán Rátóti, Maria Hafra, Adam Neinstein, Pál Makrai, Zsolt Csutak

Composers: Brent Barkman, Carl Lenox

Producers: Peter Bray, László Helle, Jim Henshaw, Stéphane Reichel

What are identical twin sisters for? Helpful and furtive surrogation inter alia, as when an impersonal student (Roth) of Renaissance art temporarily assumes the identity of her sister, a famous, hard-partying, alcoholic model (also Roth) who's reluctantly commended to a cloistered rehab clinic. In the City of Lights, that suddenly glamorous changeling is enmeshed in contention with a catty younger rival (Kerekes), a rescheduled fashion show for which her canny fitter (Beacham) prepares her, one backstair scandal involving valuable sketches stolen from the fashion mogul and designer (Richardson) for whom her celebrity sororal similitude's employed, and the potential for romance with his partner, a wealthy investor (Springfield) descended from Anglo-American aristocracy. Sinclair's eponymous novel translates entertainingly to the screen with dialogue that's as invariably and amusingly contrived as its knotty plot. Basingeresque Roth's screen presence, pulchritude, and pull don't quite offset her stiff delivery, which is overbalanced by the faux French hamminess of exuberant Richardson, smoothly sleazy Johnson, and perennially lovable Beacham. Short of stature, convincingness, or chemistry with the leading lady, weathered Springfield's gravely miscast with top billing. Rococo interiors and elegant exteriors of Budapest are also substituted for those of Paris, which is glimpsed in interstitial B-roll, some of which was clearly shot in the '80s. For its sillily scripted artifice, dubbing that's as noticeably goofy as Barkman's and Lenox's synthesized music, and wipes galore, this is a half-wedge cheesier than most of its series' erotic adventures, but no less pleasurable or prognosticable.

Writer: Helena van der Meulen

Director: Sacha Polak

Cinematographer: Daniël Bouquet

Editor: Axel Skovdal Roelofs

Players: Hannah Hoekstra, Hans Dagelet, Rifka Lodeizen, Mark Rietman, Barbara Sarafian, Eva Duijvestein, Elske Rotteveel, Maarten Heijmans, Abdullah el Baoudi, Ward Weemhoff, Ali Ben Horsting

Composer: Rutger Reinders

Producer: Stienette Bosklopper

Stages of an unstable, stunted, spurring, sportive, slutty daddy's girl (Hoekstra) are marked by her fugitive flings with a chaffing cheater (Weemhoff), an affectionate Algerian (Baoudi), one abusive roué (Horsting), and a married colleague (Rietman) of her father (Dagelet), a charming gallerist from whose example she's derived all of her dispositional and erotic expectations. His latest of many girlfriends is an auctioneer (Lodeizen) with whom he's finally found love; when she jealously, expectedly, mortifyingly lashes out from her self-destructive loneliness, their reciprocal, lifelong customs of cherishment and provocations aren't much altered. Continental cinema overabounds with soi-disant auteurs treating of aimless, oversexed young women, but Polak is a cut above most of them for her gracefully scenic handling of Van der Meulen's downbeat story, both of which draw heavily from the stylistic and thematic influence of À nos amours (Pialat's iconic, rainy shot of Sandrine Bonnaire's sulky profile is replicated in another late in this picture). Such derivativeness is overcome largely by the directrix's effectual elicitations from her tremendous cast, and especially scrawny yet stunning Hoekstra, who slips through shades of her stumbling strumpet's embarrassments, impulses, insecurities, wounds, and disappointments with a disarming expressiveness that bares her innermost vulnerability. Scenes in which she and Dagelet tenderly, often suggestively demonstrate their intimacy are remarkably moving. Her first feature disbosoms craft, insight, though not imagination that belies Polak's youth, and it's ultimately very much akin to its namesake: beautiful, but empty at its center.

Instead, watch Last Tango in Paris, À nos amours, or 36 fillette.

Writer: Simon Barrett

Director/editor: Adam Wingard

Cinematographers: Chris Hilleke, Mark Shelhorse

Players: AJ Bowen, Amy Seimetz, Joe Swanberg, Brandon Carroll, Lane Hughes, Holly Voges, Kelsey Munger, Michael Anthony Miller, Ed Hanson, Frank Stack, Whitney Moore, Gabriel Wallace, Kirstin Racicot, Travis Stevens, Cathe Frank, Melissa Boatright, Amanda Shea, Gabriel di Chiara, Ryan Beck, Simon Barrett, Michael J. Wilson, Chris Hilleke, Eric Mousel, Bill Bellinghausen, Brooke Shippee, Thomas James McBroom

Composer: Jasper Lee

Producers: Simon Barrett, Kim Sherman, Travis Stevens, E.L. Katz, Joseph McKelheer, Brad Miska, Zak Zeman, Gena Wilbur

His alcoholic ex-girlfriend (Seimetz) is still grappling with sobriety and lingering trauma while an escaped serial killer (Bowen) slaughterously amasses a fresh body count while evading police, but he's neither as avid nor unpredictable as enthusiasts of his cult fanbase.

Without their prehensile and prolific leads, Wingard's and Barrett's deviously devised yet slightly amateurish first collaboration would be among their worst. That slick professionalism and jocosity observed in You're Next (wherefor Bowen, Siemetz, Swanberg, and Barrett were disparately cast) only a year later was surely a surprise to anyone who noticed.

Recommended for a double feature with Henry: Portrait of a Serial Killer.

Writer/director: Mickey Keating

Cinematographer: Mac Fisken

Editor: Valerie Krulfeifer

Players: Dean Cates, Lauren Ashley Carter, Brian Morvant, Larry Fessenden

Composer: Giona Ostinelli

Producers: Mickey Keating, Morgan White, Sean Fowler, William Day Frank, Lauren Conoscenti

Neither a psychotherapist (Cates) nor his sluttish sister (Carter) have any reason to believe their brother, a shell-shocked Army veteran (Morvant) who's sealed with aluminum foil the windows and doors of his family's lakehouse in snowy Maine, where he's sequestered and yabbering about a dangerous creature that he's locked in the basement, which allegedly resembles another that he witnessed when he was a military test subject. Just for the sake of their intervention, they might as well let him explain. Like most of Mickey Keating's movies, his third feature is half-baked, overblown, well-made, and in desperate need of dramatic inhibition. Cates and Carter are fair foils to Morvant, whose frenzied hamminess wears on one's nerves in short order. Uncommonly clean-shaven and cast against type, Larry Fessenden is enjoyably colorful in a small, critical part. Keating and his talented crew would iterate their successes and mistakes months later by exploiting Carter's goggling, vociferous vehemence in Darling.

Recommended for a double feature with Almost Human.

Writer/director: Mickey Keating

Cinematographer: Mac Fisken

Editor: Valerie Krulfeifer

Players: Lisa Summerscales, Dean Cates, Derek Phillips, Brian Lally

Composer: Giona Ostinelli

Producers: Eric B. Fleischman, Chelsea Peters

If we must live in a cinematic era wherein epigons rather than auteurs prevail, we could fare worse than to witness the motion pictures of Joe Begos, Panos Cosmatos, or Blumhouse alumnus Mickey Keating, in whose first, flattest feature a flirtatious woman (Summerscales) who's separated from her husband (Cates) calls him to her aid at a southern Texan motel after stabbing a drunken lout (Phillips) in self-defense during Halloween and a lunar perigee. Their situation worsens after their viewing of her assailant's videorecordings uncovers his membership in a masked, Satanic cult who've a routine of human sacrifice.

Like most of Keating's sequent (and briefer) features, this would've been better as a short, for which funding and distribution are admittedly procured with greater difficulty. He sets his shots and guides his performers well, but Keating's faculties didn't offset the deficiencies of his woefully underdeveloped script -- a fault that's observable in most of his movies.

Writers: Joyce Carol Oates, Tom Cole

Director: Joyce Chopra

Cinematographer: James Glennon

Editor: Patrick Dodd

Players: Laura Dern, Treat Williams, Mary Kay Place, Elizabeth Berridge, Margaret Welsh, Sara Inglis, Levon Helm, William Ragsdale, David Berridge, Geoff Hoyle, Joy Carlin, Mark McKay

Composers: Russ Kunkel, George Massenburg, Bill Payne

Producers: Martin Rosen, Timothy Marx, Lindsay Law

By dint of a screenplay with the befitting elegance and mystery that are nigh-absent in Tom Cole's, Joyce Carol Oates's oft-published, exhaustively analyzed, and multiply allegorical short story Where Are You Going, Where Have You Been? might've been more succinctly and potently dramatized. With and without her friends (Welsh, Inglis), a flighty, flirty, frivolous teenager (Dern) basks at a beach, squabbles with her resentful and concerned mother (Place), contemns her plain, antipodally obedient big sister (Berridge), loiters and shops and boywatches at a local mall, and makes out with cute older guys (Ragsdale, Berridge) who they meet at a burger joint. Whilst home alone, she's blandished, seduced, confronted, threatened, ultimately coerced by a cheesy, sleazy lothario (Williams) in a convertible Le Mans, who has plenty to propose, and won't take no for an answer. Chopra's direction is bewilderingly erratic: alternately artful and amateurish, and at its best engenders unforgettably efficacious intimacy, tension, and truly provocative ambiguity. Her outstanding cast do her no small credit for their verisimilar subtlety; though she's flagrantly miscast (and could clearly pass for a tricenarian), Dern perfectly exudes adolescent vulnerableness, choler, and joyance, esp. when interacting with broodily bitter Berridge and Williams, who bestows to his nearly burlesqued mischaracterization an allurement, alacrity, and ardor of impressive radiance. Partly for Patrick Dodd's sloppy editing of its first two acts and Cole's often painfully patent and palliative misadaptation of Oates's graceful implications regarding innocence lost, this isn't the masterpiece that Chopra's feminist coevals insist that it is, but it's among only a few pictures to so strikingly narrate some dubiety of consent.

Writer/director: Christina Wayne

Cinematographer: Stephen Kazmierski

Editor: Ray Hubley

Players: Dominique Swain, Brad Renfro, Bijou Phillips, Alberta Watson, Mischa Barton, Jacob Pitts, Nora Zehetner, Lacey Chabert, Scott Thompson, Myles Jeffrey, Michael Murphy, Chelse Swain, Sherry Miller, Peter Snider, Marcia Bennett, Mairon Bennett, Liz Gordon, Tannis Burnett

Composer: Jeehun Hwang

Producer: Derrick Tseng, Diane Isaacs, Nile Niami, Sam Gaglani, Patrick D. Cheh, Jeremy Lappen, Margot Lulick, Clark Peterson

With and without stereotypically slutty (Phillips), uptight (Barton), snotty (Zehetner), and nerdy (Chabert) friends, an insecure, pouty private school's junior (Swain) in NYC navigates clichéd situations involving peer pressure, parties, narcotics, theft, gossip, her sternly solicitous mother (Watson) and absent father (Murphy), and her initially unrequited crush on a nearby school's handsome, addled student (Renfro). Notwithstanding a few amateurish shots, Wayne's supervision of her sole directorial effort is passable; would that the same could be said for her timeworn script, which (especially for lunkily pretty Swain's periodic voice-over) plays like mad libs on themes of teen angst and self-destruction. Acting varies greatly here, but most of the cast cope well with Wayne's contrived dialog and few flaccid attempts at humor, none of which are as funny as Barton's horrendously affected English accent, or fantastically anachronistic tribulations attending casual anti-Jewish biases, which are slightly less incongruent in Manhattan c.2000 than they might be in Jerusalem. One blond, upper-class object of envy is incarnated by Swain's sister Chelse, and insurpassably gay former Kid in the Hall Thompson makes the most of his sordid part as a queer, middle-aged drug dealer who consorts with rich kids for illicit opportunities. This was among the last of Swain's numerous failed vehicles, absurdly mismarketed as a sex comedy and blazoned with Melanie Griffith's name for her negligible cameo. Effectively typecast Renfro and Phillips perform as well here as they would in similar roles of Larry Clark's coetaneous true crime Bully.

Writer: Barry Clark

Director: Robert Anderson

Cinematographer: J. Barry Herron

Editor: William M. Anderson

Players: Debbie Osborne, Nancy Ison, Max Manning, Sue Allen, Cheryl Powell, Tom Benko, Alice Friedland

Composer: Robert O. Ragland

Producers: Robert Anderson, Terry Anderson, William M. Anderson

Glimpses of the debauchery for which her licentious half-sister (Ison) is locally known intrigue a cute, hesitant, adolescent virgin (Osborne), whose bloom isn't at all noticed by or discussed with her absent, adultering, alcoholic parents (Manning, Allen). Antecedent to its laughably tragic ending, not much other than heavy petting and occasional intercourse between young women and seedy older men occurs in Anderson's dumb, dull, dumpy, softcore drama, the scarcely plotted vapidity of which emphasizes the emptiness of profligacy. His frequently and flagrantly dubbed cast overplays and underplays risibly; only Osborne has some notion of how to act. Ergo, nothing's wasted on Clark's brainless script, dialogue of which is peppered with groovy boomerisms, man. Taken as a snapshot of two oversexed, unreflective generations in their haze of suburban malaise, that zeitgeist of American society steeped in dysfunctional postwar prosperity is here blurrily preserved.

Writer/director: Isaac Webb

Cinematographer: Alejandro Martínez

Editor: John Gilroy

Players: Elisabeth Shue, Steven Mackintosh, Kathleen Chalfant, Nikita, Blair Brown

Composer: John Frizzell

Producers: Rick Schwartz, Lemore Syvan, Graham King, Bill Block, Ben Waisbren, Ethan Smith

Quality composition and one cleverly concocted, schizoidally recursive sequence can't counterbalance the genre clichés (spooky doll, dead pet (Nikita), expatriate and seemingly sinister nanny (Chalfant), overreactive hysteria) or inconsequential activity that pads the runtime of Isaac Webb's only feature, an antinatal melodrama masquerading as a horror flick. Her troublous pregnancy anticipates the postpartum distress of a contemporary dancer (Shue) who's relocated to an exurban mansion with her lawyering husband (Mackintosh), where she makes a mess of what could be idyllic domesticity. Briarcliff Manor is an attractive backdrop, and more interesting than either Webb's stale screenplay or an inconsistent performance by Shue, who nails her niceties but overacts most of her major moments. John Frizzell's score encompasses some fine themes, but its incessance is wearisome. Webb isn't without directorial talent, but he ought've delegated authorial duties to a screenwriter who could've retained his few good ideas, dumped his chaff, and penned a leaner, quieter script contributing to any suspense whatsoever, wherein its maternal protagonist isn't merely a nutty incompetent.

Instead, watch Rosemary's Baby or Images.

Writers: David Baughn, Herb Freed, Anne Marisse

Director: Herb Freed

Cinematographer: Daniel Yarussi

Editor: Martin Jay Sadoff

Players: Christopher George, Patch Mackenzie, E. Danny Murphy, Michael Pataki, E. J. Peaker, Carmen Argenziano, Richard Balin, Denise Cheshire, Linnea Quigley, Billy Hufsey, Tom Hintnaus, Virgil Frye, Vanna White, Karen Abbott, Linda Shayne, Carl Rey, Erica Hope, Beverly Dixon, Hal Bokar, Ruth Ann Llorens

Composer: Arthur Kempel

Producers: David Baughn, Herb Freed

On leave from active duty to attend the graduational ceremony where a deceased track star (Llorens) is to be commemorated, a naval ensign (Mackenzie) arrives just as athletic seniors who competed in her late sister's track team are sequently slain during the week preceding graduation. Herb Freed's commercially successful, critically lambasted, atrociously screenwritten and shot slasher is among the worst of its genre, a bloated, sluggish, unscary mess produced to bloodily exploit yet another festive occasion. Gruff George capably fills the sneakers of the school's mispunished coach and foremost red herring, and Pataki lends amusing personality to a much-loathed, oleaginous principal, as does Balin as one flamboyant, toupéed music teacher and summery lounge singer. Otherwise, most of the cast is horrendous; Mackenzie in particular is so aggravatingly awful that she can't even run believably, and her haughtily overwrought delivery actually worsens the inanity of her dialogue. Those fond of scream queen Quigley and Wheel of Fortune's yearslong hostess White may enjoy them at their respectively sluttily and goofily cutest. Martin Jay Sadoff's fastidiously ambitious editing is interesting for daringly momentary intercuts and omissions, but it can't countervail the unprofessional crudity of Freed's composition. Not recommended.

Writers: Todd Farmer, Zane Smith

Director: Patrick Lussier

Cinematographer: Brian Pearson

Editors: Cynthia Ludwig, Patrick Lussier

Players: Jensen Ackles, Jaime King, Kerr Smith, Edi Gathegi, Tom Atkins, Kevin Tighe, Megan Boone, Chris Carnel, Betsy Rue, Todd Farmer, Richard John Walters, Karen Baum, Joy de la Paz, Marc Macaulay, Jeff Hochendoner, Bingo O'Malley, Liam Rhodes, Michael McKee, Andrew Larson, Jarrod DiGiorgi, Selene Luna, Cherie McClain, Tim Hartman, Ruth Flaherty, Jerry Johnston, Mightie Louis Greenberg, Sam Harris, William Kania, Nick Marcucci

Composer: Michael Wandmacher

Producers: Jack L. Murray, Jonathan McCoy, John Dunning, André Link, Michael Paseornek, Hernany Perla, John Sacchi

In observance of the amative, titular holiday and remembrance of the unhinged miner (Richard John Walters) whose rampage a decade earlier laid low over a score of residents in his town, another killer (Chris Carnel) is cumulating corses anew. He has means, motive, and opportunity aplenty, so the repairing scion (Jensen Ackles) of the mine's late owner is probably responsible.

Even those of us who love it won't pretend that the Canadian, working-class slasher of '81 was a great film, but it contains everything that this drab, trashier remake hasn't: fine, stygian photography, effective suspense, actors who performed well and looked great, and George Mihalka's stylish operation. One can't expect much from either a remake or a vehicle for gimmicky gore and 3D effects during another of that trend's resurgences, but one might've hoped that Lussier could replicate anything substantive from the panache of Mihalka's low-budget hit.

Writer: William T. Naud

Director: Dusty Nelson

Cinematographers: Eric Cayla, Richard Clabaugh

Editor: Carole A. Kenneally

Players: Elizabeth Kaitan, John Tyler, Lisa Beth Wilson, Waide Aaron Riddle, Russ Tamblyn, Stan Hurwitz, Rhonda Dorton, Ed Wright, Shawn Eisner, David Flynn, Lois Masten Ewing, Lisa Randolph, Scott Harrison, Keith Burns, Carla Baron, Shannon McLeod

Composers: Bob Mamet, Gary Stockdale, Kevin Klingler

Producers: Roy McAree, William J. Males, Michael Scordino

One rich, deranged upperclassman (Hurwitz) rapes a sweet collegian (Kaitan), who unseriously pays an underfed witch (Wilson, practicing sortilege in a garage draped with crudely painted polyester studded with rhinestones, which adjoins a shabby suburban house) to exact revenge on those who've upset her. Mimetical demonomagy that gorily greases the gentle student's transgressor and his abettors (Wright, Eisner) then supererogatorily targets her lecherous professor of theater (Tamblyn), an ugly nerd (Riddle) who's straining to nullify the enchantress's incantations with lunar white magic, and her boyfriend (Tyler), a rock band's keyboardist who will not shut up for one second to heed anyone. Plenty of inadvertently humorous delivery and awkward moments enliven this schlocky horror, which is notable for its shoddily gooey and animated SFX, and impenetrably senseless characters. Nelson sets his shots sufficiently, but clearly wasn't required to coach his hammy cast headed by gawky, photogenic, Hannahish Kaitan, a bit player in major pictures and leggy star of no few B-movies. At his cheesiest a couple years before his career was revived by David Lynch and Mark Frost, Tamblyn is the only capable histrion here, but he brings little presence to his dramatic dissolute. Such bad movies retain value as unpretentious entertainment for those who enjoy their quirks, flaws, and underbudgeted audacity.

Writer/director: Edgar Michael Bravo

Cinematographer: Rush Hamden

Editor: Jason Rose

Players: Kelly-Ann Tursi, Joseph Luckay, Paul Nguyen, Jon Morgan Woodward, John Buckley Gordon, Kalena Knox, Phillip Gay

Composer: Nima Fakhrara

Producers: Levi Obery, John Paul Rice, Lota Hairston-Hadley

They don't incur the physical wear or injuries of prostitutional acokoinonia, but marginally profitable sessions wherein a young dominatrix (Tursi) indulges the footling fetishes of her clients (Woodward, Luckay, Gordon) sans sex, smooching, or nudity for absurdly affordable rates hardly satisfy her or advance her ambition to invest in realty. Neither she nor her pouting, porting, protective partner (Nguyen) contend well with the instability of their clientele in hideous Hollywood. Writer/director Bravo perfunctorily managed his uninteresting, sub-erotic, nonsensical drama with slightly more competency than that afforded to the average shiteo production, but in spite of some unintentionally funny moments, one needs patience to sit through such slog of an attractive lady interacting transactionally with indecisive, harebrained lowlives. Bitchily stiff Tursi's screen presence helps her to carry her simple protagonist, but her performance wavers between convincing restraint and spiritless ineptitude, which is more than could be said for her wooden co-stars. Avoid.

© 2024, 2025 Robert Buchanan